641: The Walls

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

Mohamedsalem is 33. And his parents want him to call his cousins on the phone. He doesn't want to. He doesn't like to. And I have to say, I'm with him. He's got a really good excuse.

Mohamedsalem

[SIGHS] I just grew up never knowing them. For me, I need to spend time with them to start to be attached to them.

Ira Glass

No, I understand. They're like strangers to you.

Mohamedsalem

Yes, exactly.

Ira Glass

He never got to know any of his relatives because Morocco built a wall 1,700 miles long across the desert. It's actually several walls of piled up sand, plus ditches in between the walls, plus barbed wire, plus, reportedly, seven million landmines, plus 120,000 soldiers separating the rest of his family, who were in Western Sahara, from the place where Mohamedsalem was born and still lives today, a massive refugee settlement with an estimated 165,000 people in it on the other side of the wall. So he has all these cousins from eight aunts and uncles. And--

Mohamedsalem

I would never met them. There is nothing in common. We haven't shared anything. I know their names, and I know I have a relative. But--

Ira Glass

That must be so frustrating for your parents.

Mohamedsalem

[LAUGHS] All the time they try to get me to call them and talk to them, but what should we talk about? And what do we have in common that we can talk about if we finish the initial greeting? And I feel guilty about it and bad about it, but it's just I don't know what to do about it.

Ira Glass

Not that his parents get this.

Mohamedsalem

They are mad. But part of the blame belongs to them, to the fact that the occupation and the family separation. And I shouldn't be totally the one to take all the responsibility for everything.

Ira Glass

Oh, I see. You're saying, don't blame me. There's an entire international situation here. I am not personally to blame for this.

Mohamedsalem

Yeah, yeah. I didn't choose to leave away from them. And if I have the chance, I would love to be with them and get to know them.

Ira Glass

But the wall between the refugee camp where he's lived his life and the area where his family's from, where he says they belong, that wall is the central fact of his life, the rock on which everything else is built. If the wall weren't there, instead of his current life, where he spends his days doing politics, trying to draw the world's attention to the situation his people are in--

Mohamedsalem

I for sure would have nothing to do with politics. And I wish I had the option and the choice to care about silly things like the rest of the people. I love swimming. And I have done it just like three or four times, once when I was a child.

Ira Glass

And there's no place to swim in the refugee camp.

Mohamedsalem

No, no, no, no, no, no, there isn't. There isn't.

Ira Glass

There's a 1,700 mile wall between him and the ocean. When somebody builds a wall, we readjust our lives around that wall.

Conor Garrett

So just tell us what you're doing here.

Man

I'm just closing the main gate until tomorrow morning.

Conor Garrett

So what's this gate made of?

Man

I don't know.

[BANGING]

Conor Garrett

What is that? Steel?

Man

Yeah.

Conor Garrett

With big spikes on the top.

Ira Glass

In Belfast, Northern Ireland, it's been 20 years since peace was declared between Protestants and Catholics. But there are still these tall walls, some of them 50 feet high, that separate their neighborhoods with a few gates that allow traffic and pedestrians through. It's 6:30 at night, and the guard is closing the Northumberland Gate for the evening. It will reopen at 6:30 in the morning. Producer Conor Garrett talked to him.

Conor Garrett

They're just waving people through. You can see people are rushing before they close up for the day.

Man

Yeah. I could actually time them. I could actually time them.

Conor Garrett

You mean you can time them? You know what time they're going to come through?

Man

Yeah. Yeah.

Ira Glass

People are so used to having the walls and so nervous about the violence that might break out if they were torn down that two decades after the conflict officially ended when there was a modest proposal not to tear the walls down but to simply replace the sheet of steel that was the gate at the Workman Avenue crossing with a gate that is steel bars that you can see through to the other side, that took 18 months to convince local residents of. Ian McLaughlin is one of the organizers who pushed for that change.

Ian Mclaughlin

It was a very long and drawn out process because you have to take into account people's fears. The vast majority of deaths which occurred during the conflict occurred where these structures were built. And the point I make is that, primarily for some of our elderly residents who live in these neighborhoods, a death of a family member that may have happened-- I don't know-- 30 or 40 years ago, it's as though it happened 30 days ago. So any conversation or any suggestion of a removal of that structure, it actually, to this day, traumatizes these families.

I think you have to realize, in people's mindsets, if you have lived in the same neighborhood for 40 years, and every single day when you wake up, the first thing you see when you draw your blinds is this structure at the bottom of your garden or your alleyway, if you're waking up one morning and that structure's gone, how would you feel?

Ira Glass

Once a wall is up, it seems hard to tear down. And more are going up these days around the world. India's building a 2,500 mile barbed wire fence on the border with Bangladesh. Kenya's built just a few miles of what it hopes will be hundreds of miles of wall on the Somalia border. Israel had 300 miles of walls between itself and the West Bank and then added another 245 miles on the border with Egypt in 2013.

The main reason walls are going up around the world right now is to stop unwanted immigrants. That's the reason for the wall that was just finished between Turkey and Syria, which is nearly 500 miles long. It's there to block terrorists and Syrian refugees. Journalist Maya talked to me from Kilis.

Maya

We are at the border gates. Every Syrian who you speak to who has managed to cross the wall speaks about having been shot at either with rubber bullets or with real bullets. And Syrians have been killed, yes.

Ira Glass

Stopping immigrants, of course, is the reason for the wall that President Trump wants to build on the Mexican border, the one he shut down the government over.

President Trump

Look at all of the countries that have walls. And they work, 100%. A wall is a wall.

Ira Glass

That was at his cabinet meeting this week. In San Diego last year, he inspected prototypes of different walls for the border.

President Trump

The round piece that you see up here or you see more clearly back there, the larger it is, the better it is because it's very hard to get over the top. These are like professional mountain climbers. They're incredible climbers. They can't climb some of these walls. Some of them, they can. Those are the walls we're not using.

Ira Glass

Stopping immigrants is the reason that Norway just built a wall that is a measly 650 feet long at the very tippy top of Norway at the Russian border. I talked to the mayor of the town on the Norwegian side of that border, Mayor Rune Rafaelsen, of the town of Kirkenes.

Ira Glass

Can you see Russia from your house?

Rune Rafaelsen

Not from my house, no. But from my cabin, I can see Russia. [LAUGHS] Yeah.

Ira Glass

If I could just talk to the liberals in our audience for a second, I know when you guys think of the Scandinavian governments, they seem so competent and functional with their universal health care and their broad social safety nets. And I just want to say, perhaps it will be comforting to you to hear that this particular project was just as bumbling as anything we do here in the United States. They built their fence a full year after migrants had already stopped trying to cross that particular border, so there were no migrants to stop. They accidentally started construction too close to the Russian border, then had to tear it down and move it back a foot and a half.

And they built their fence right next to a fence that Russia already had at the very same border, a way more effective fence that stretches 120 miles. Remember, the Norwegian fence is only 650 feet long. As the mayor pointed out, refugees will be able to simply walk around a fence that is that short. So why build it?

Rune Rafaelsen

Because the government wanted to do something, to say that we are building walls up, way before it was inspired by Mr. Trump and the walls to Mexico. I don't know. So it's just a symbol. It has no effect regarding protecting Norway from refugees at all, so people are laughing about it.

Ira Glass

Wait. I still feel confused. If there's already a fence on the Russian side, why would there need to be a second fence?

Rune Rafaelsen

Yeah. [CHUCKLES] I agree. You'd have to ask the recent prime minister about that. I don't understand why they have built this fence. It's very, very odd. They're very comic.

Ira Glass

A wall, apparently, just has its own gravitational pull that warps the logic of the world around it. And once the wall is up and is a fact on the landscape, it alters the human behavior on either side of it. At that point, it's like we accommodate the wall, and definitely not the other way around. We are the ivy that grows on it. It is the immovable object.

Today on our program, as our government fights over whether or not to build a big, beautiful wall that apparently Mexico is not going to pay for, we have stories about people and walls all over the globe. We hear about kids who use a border wall as a tool in their family relationships, people who devote themselves to conquering walls, and a wall that supposedly can only be seen from one side, and not the other-- no kidding.

From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Stay with us.

Act One: Just Another Kind of Outdoor Game

Ira Glass

Act One, "Just Another Kind Of Outdoor Game."

So when we were looking at border walls and fences around the world, one in particular stood out to us because if there were ever a place where you think you could build a physical barrier between two places and have it work, this would be the place. The fences are around the Spanish cities of Malilla and Ceuta. Now, the interesting thing about these Spanish cities is they are actually in Africa.

Right on the Northern coast of Africa, right there on the mainland, right on the edge of the water in what would otherwise be the country of Morocco, there are these two little dots, two cities that are officially part of Spain. Ceuta and Malilla are both very small. Ceuta is about seven square miles. Malilla is less than five square miles. And if you can make it into either of these cities from the rest of Africa, you're on European soil. You can try to claim asylum, or find some other way to stay and live in Europe.

But the Spanish government, with the assistance of the Moroccan government, has built a very impressive barrier. Around Ceuta, there are two layers of fencing almost 20 feet high with razor wire on the top. Around Malilla, there are four fences and a trench, basically a moat without water in it-- it's two meters deep-- also infrared cameras, and of course, guards.

And what has happened is that this has created a perverse and pretty dangerous obstacle course. Because, of course, people try to storm the barrier, sometimes in huge groups trying to get through it all at once, any way they can.

[SHOUTING]

Our producer, David Kestenbaum, talked to one man who thought he could make it.

David Kestenbaum

David is from Cameroon. And when I asked him to say his full name, just so I didn't mess it up, he gave this surprisingly long answer.

David

[NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]

David Kestenbaum

I couldn't tell what was going on, because we were doing the interview through an interpreter. But it turns out he was explaining how he would introduce himself as an African.

David

[NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]

David Kestenbaum

The names of his grandparents, and their parents, and theirs.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

David Kestenbaum

Those are the 23 generations of my grandparents, he says, 23 generations of names. And yet despite all that history, in September of 2013, David decided to leave Cameroon and try to make it to Europe. He was 25 years old. David describes the whole thing almost as if you were a kid heading out on an adventure in some old novel.

Unlike a lot of people trying to get from Africa to Europe, he said he wasn't persecuted back home. He wasn't starving. He wasn't fleeing violence. He was just curious about the world and excited to see it. He wanted to live in a place with more opportunity, so he threw some stuff in a little backpack and he hit the road. He was well into his journey in Algeria when he first heard about the fences around Ceuta and Malilla.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

Because there we had internet access, and we could see how people were trying to jump this fence and all that.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

At the beginning, my opinion was, well, you know, I'm a pretty brave guy. And when I see something like that-- I like challenges. I thought I would do it in one try. I'm going to take it on with a lot of optimism, because that's the type of person I am.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

I usually do things the first time I try them. I don't do them two or three times. So I thought this was going to be the case with this fence.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

David Kestenbaum

I've watched some of these videos. There are some brutal ones-- people with their hands sliced open from the razor wire, sometimes being hit by guards. But there are ones that, if you are preparing to try something like this, might give you hope.

Crowd

[SHOUTING]

David Kestenbaum

This one starts at a tense moment. There are bunch of men sitting on top of the last of the fences. Below them is Spanish soil, but also the Spanish police. In theory, the guys should be able to drop down and apply for asylum. But there are lots of reports of Spanish border guards grabbing people, unlocking a gate in the fence, and returning them to the other side. So the men on the fence want to get down somehow, avoid the guards, and run into town.

Crowd

[SHOUTING]

David Kestenbaum

Suddenly, one man drops down off the fence, then another. It's like they've got some plan. And apparently they do, because the two of them link arms. Then another guy joins them and another. They keep linking up, like it's a rugby scrum.

At this point, the police move in they're wearing vests and helmets. Some have those transparent shields you see in crowd control situations. And you can see the police are now in kind of a bind. It's going to be hard to pry these guys apart now that they've become this giant organism.

So the police do this thing that also seems smart. They form a human ring around the men to contain them. And for a moment, it seems like a stalemate.

But then the scrum starts to rotate, which makes them harder to contain. And a gap opens up in the ring of police. Then one guy from the scrum breaks off and starts sprinting. Then another spins off, and another.

Crowd

[CHEERING]

David Kestenbaum

They run across this open field into town, and finally to the official immigration center where they celebrate like a team that's just captured the flag.

Crowd

[CHEERING]

David Kestenbaum

I don't know how many of these people were granted asylum or allowed to stay. But can I just say there is something crazy about a system where countries build super tall, multi-layer razor wire fences that you are definitely not supposed to cross. But if you do cross them, well, maybe you can stay. It's as if Spain is saying, this is who we want to immigrate-- people who are really good at climbing fences.

David figured he had a pretty good chance of getting over the fences. He was young. He felt strong. He saw them up close soon after he got to Morocco. He made his way to this forest where he heard people camped out before attempting to cross. You could see Malilla from there, this piece of Europe surrounded by fencing.

Interpreter

They said to me, look, over there. That's Malilla.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

David Kestenbaum

In the woods, there was this whole community of people. They'd organized themselves by country. There was a group from Mali and Gambia, Guinea, and one from his country, Cameroon. He slept with them that night.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And that night, it really rained. And since I was new, I didn't have any place to sleep. And I didn't have any place to hide from all the water that was falling out of the sky.

David Kestenbaum

The next night, David and a small group he'd been traveling with went to check out the fences. But David said they didn't really know what they were doing. When they got there, they saw Moroccan border guards. David and the others figured, well, we'll just wait till they move. But hours went by. They waited until 2:00 AM, but always, there were guards.

The next time, he had better luck. One of the tricks the people in the forest told him was to go in large groups. If you've got the numbers, they can't catch all of you. So this time, David goes with a big group of 200 or 300 other people. It was early in the morning, 4:00 or 5:00 AM. They run toward the fences.

The first obstacle, before you can even get to the fences, is that trench. It's pretty deep, David says. He drops down into it OK, but getting out is hard. It's like six or seven feet straight up. He says everyone kind of helps each other. One person gets up, then pulls the next one up.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

I tried to get out of there, and there were Moroccan military people who were throwing stones. And there was a lot of noise. And people were moving around, and there was blood. And it was difficult to get out.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And then I was climbing up the other side. And then I climbed up the first barrier. And I got to the second barrier, and then I said, OK, I finished that. I'm going to go to the third barrier.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

I don't know how to express it, but it was something strange. I was thinking, I'm going to do it. Then I thought, I can't do it. And then I was doing it, so I said, well, this is how it's done. I'm doing it. I'm doing it. But I don't know how to express it. That's the truth.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

David Kestenbaum

Did it feel like a crazy sport?

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

Yeah, exactly. That's exactly what it is, the way you put it.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

It was a weird sport.

David Kestenbaum

I usually think of a border wall or a fence as this thing that's supposed to stop someone. But as David was discovering, that's not how these things are actually designed. His opponents had a strategy too.

The Malilla border is an example of something called defense in depth. In the US, it's used around nuclear facilities. The idea is to have many layers. Each can be beat, but they slow you down enough so that, before you can get to the other side, the guards are there. In this case, to pick you up and send you back to start.

That's what happened to David that day. The guards got him before he could clear the final fence, and they sent him back to Morocco. He was frustrated, but also felt kind of good. He'd made it to the third fence on his first try.

David returned to the camps in the forest, which he says is OK. But I think it's not what a lot of people would call OK. He had to dig around in trash cans for food. And sometimes after they'd gone to sleep, the Moroccan police would come and chase them out, destroy what they'd set up.

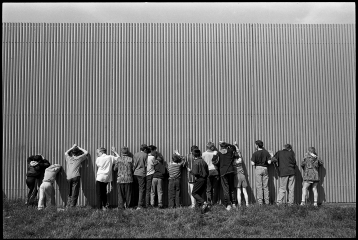

When there was downtime, people would sometimes sit all facing the same direction and just kind of stare out at Malilla and talk about how to get past those damn fences. There were rules that have been passed down by people who'd gone before them with the goal of not making things harder for the next people trying to cross. One of the rules was no weapons-- another, no cutting the fence.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

We decided that it wasn't a good strategy because, at the end of the day, our goal was to be accepted by the Spaniards on the other side.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

So we didn't want to use knives, and we couldn't cut the fence.

David Kestenbaum

They tried over and over, but it seemed impossible to beat the guards. They had cameras that could see at night and helicopters. David met people who'd been living in the forest for four or five years who still had never made it to Europe.

David checked out the fences around Ceuta, the other city, but again, no luck. He tried 20 times, 30 times. A year pased. At some point, it started to feel kind of crazy that this is what his life had become, trying to get over this barrier to this little piece of land.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

There were times when it did appear absurd to me. Why am I doing this? What good is this? Especially when I experienced the failure, and I thought about just abandoning everything, and I would cry.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

But then you rest up two or three days. And once again, you think in an optimistic fashion. And I got my energy back.

David Kestenbaum

I wondered what all this looked like from the other side of the fence, to live in one of these cities five or seven square miles in size with fences around it, where in some years, you get people rushing up every few weeks, this whole mass of people outside trying to get in. There's this one photo from the Spanish side of two people playing golf. They're standing on this lush green fairway, palm trees. One of them, a woman, is teeing off in a bright white golf outfit.

And right behind them, there's the fence. And on top of the fence, about a dozen people straddling it. I couldn't find any surveys of how people in the towns felt about the fences. But one journalist who lives in Malilla told me that photo is kind of the way it is for a lot of people. They're used to it now.

When the fences started being built in the '90s, some people thought they were ugly or sad. But then the fences became something else. They became invisible.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

It's something more than a fence. I know it may seem silly, but--

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

There is something mystical in this fence. I've seen people who, when they get in front of the fence, they can't move.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

I imagine that, if there are people from throughout the world who get together to make a fence, there must be a spirit inside the fence that tries to prevent things.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

It's really something very powerful. It's not just a fence.

David Kestenbaum

Even a fence with a spirit in it is still a fence. And as with a lot of fences, if you follow them far enough, there is a place where they end. Malilla and Ceuta are not totally surrounded. They're on the coast. And where the fences hit the water, they stop. They go out a ways into the water, but then stop.

These places, of course, are very heavily guarded. And in the previous year, a bunch of people had died trying to cross this way. The Spanish police used tear gas and rubber bullets. At least 15 people drowned. And David can't swim.

But one day, in the forest around Ceuta, he runs into a group of people who want to try this place where the fence ends. By this time, he's been at it for a while. He knows the way. He helps lead them there.

There's no trench here and only a single fence. And so when it's dark out, David and a group sneak up to it through this wooded area. There are over a hundred of them, and they start running along the fence, trying to get to the beach and finally where it extends into the water.

When they reach the beach, some people start trying to climb the fence. Guards are gathering, but David notices they aren't doing the thing that he's had problems with in the past. They aren't hitting people's fingers as they climb. So up he goes.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

I put one finger on, and I put one hand on. Then I put one leg up. And I got up to the point where there were the knives.

David Kestenbaum

He means the razor wire at the top.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And I tried to get higher up, but these knives we're grabbing at my clothes. And I had a backpack on, so I had to go down.

David Kestenbaum

But not all the way down. David and the others stay on the fence. They're just below the very top, maybe 18 feet off the ground. And they start clambering sideways, horizontally along the fence trying to get to the water.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And there were two kids in front of us. One of them was really young. He was like 13 or 14.

David Kestenbaum

They were moving very slowly.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And someone behind me said, hurry up, hurry up. And I said, look, the boys in front of us cannot go fast. We've got to go step by step.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

If we make it to the water, we'll be OK.

David Kestenbaum

They get to the end of the fence. There are two people ahead of David. The first one jumps down.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And he fell into the water on the Moroccan side. And he was immediately picked up by the Moroccan soldiers. They picked him up and put him in a boat.

David Kestenbaum

Which seemed bad. A Moroccan guard would keep him in Morocco. The next guy is the kid in front of David. He jumps down onto the rocks at the base of the fence.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And very quickly, hit the ground. And as soon as he hit the ground, the civil guard picked him up and put him aside.

David Kestenbaum

David is next in line, the third to try.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

At the moment that I saw the civil guard people moving two or three steps away, I went down immediately, just like the kid did. But as soon as I hit the ground--

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

I went right into the water.

David Kestenbaum

Then others make it into the water. They sit on this big rock.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

The little kid, who the police, the civil guard, had picked up and already had his hands tied behind his back, tried to escape and make it into the water.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And just to show, one of us was brave enough to go into the water, and he saved him and brought him over to the stone.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

So then we were singing and shouting.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

The civil guard was saying--

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

Get out of the water. Come out of the water, and nothing's going to happen to you.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And there were many negotiations to get us out of the water.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

And we didn't want to get out.

David Kestenbaum

This goes on for hours. They're cold, but singing and shouting, waiting for the city to wake up, hoping someone will come and help them-- the Red Cross, journalists. Eventually, they do get out of the water. They're taken to a police station and fingerprinted. David figured he'd be sent back to Morocco like all the other times.

The police station was right there on the border. But it didn't happen. Instead, someone got him some food and a place to sleep. After almost two years of attempts, he'd made it. He felt joy, like, is this really happening? For a couple of days-- and then he felt something else.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

When I realized that I had made it, it was like a vacuum.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

That's the truth.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

When we are in Morocco, we think that whenever I manage to get there, I'm going to be very happy.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

But once you make it--

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

--you don't feel anything.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Interpreter

The feeling ends.

David Kestenbaum

David is in Madrid now. In a little bit, he'll be able to apply for residency so he can work. After almost two years thinking about the fence, he doesn't anymore. It was just a barrier, one among many.

Ira Glass

David Kestenbaum is one of the producers of our program.

David

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Ira Glass

David from that story is trying to make it as a musician. He wrote this song about the border fence.

[MUSIC - "BARRIER DE POLICE" BY DAVID]

David

(NON-ENGLISH SINGING)

Ira Glass

Coming up, the wall that is 150 miles long and completely invisible from one of its sides. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio when our program continues.

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Today's program, "The Walls." We have stories from around the globe looking at the way that life morphs and adapts around any wall that gets built anywhere. A version of today's program was first broadcast last year, but we thought we would update and bring it back with our government shut down over a wall.

And one thing that I've found myself thinking about a lot these last few weeks has been the president's promise to have Mexico pay for the wall. And I think a lot of people don't remember that that just wasn't a thing that was said in rallies. There was an actual step by step plan on how to do it. And I've wondered, whatever happened to that?

Robert Costa

It's the long forgotten plan from the Trump campaign. We talk now like this plan never even existed.

Ira Glass

This is Robert Costa, national political reporter for the Washington Post. He says that when he and Bob Woodward asked then-candidate Trump in 2016 for details about exactly how he would pay for his wall, to their surprise, two days later, they got this step by step memo outlining how it would happen, written, he says, by Stephen Miller, now one of the president's top aides.

Robert Costa

This is something that the Trump campaign was under intense pressure during the primary season to prove that, in some way, it had a serious proposal for getting Mexico to pay for the wall. And this is what they came up with.

Ira Glass

Here's the plan. They say that under the Patriot Act, the president has powers to do all kinds of things, including, if he wants to, he can make it impossible for undocumented Mexicans living here to wire money home to Mexico. And it's a lot of money, the memo says, $24 billion a year. The actual number is probably much smaller than that, but still in the billions, significant to the Mexican economy.

Mexico, as the memo notes, would not like this. And so the memo says we would tell the Mexican government that it could avoid all this unpleasantness if it would just send us $5 to $10 billion for the wall. And then we won't make the change to our regulations. We will let people wire money home to Mexico.

Robert Costa

It said in typical language by President Trump, it's, quote, "an easy decision for Mexico to make," and that all they need to do is make a, quote, "one-time payment of $5 to 10 billion for the wall," and then they could walk away.

Ira Glass

If that didn't work, the memo lists other threats that we could make. Trade tariffs-- we could cancel work and tourist visas. We could charge higher visa fees, all with the idea that this would force Mexico to cough up billions for the wall.

Ira Glass

Do we know if they tried to do any of this once they got into office?

Robert Costa

We're actually poking around about that at the Washington Post. It seems like John Kelly, when he was head of DHS, and Kirstjen Nielsen, now head of DHS, they have not pursued this kind of policy to an extent. But the idea that it's floating around in Trump circles remains. Bannon always would hover it out there in 2017 when he was in the White House as something that would maybe be brought up. And it could still be brought up. He believes he has sweeping executive authority to do this sort of thing.

There have been bills in Congress to do a more straightforward version of this by just taxing the money that gets wired to Mexico and do some of the other things that the memo suggests. There was a bill in 2017, another in 2018. Neither picked up many co-sponsors or ever got to a vote.

On Friday, the president said that he might declare a state of emergency to pay for his border wall, which would give him a bunch of options, a bunch of powers, none of them apparently related to this memo or Mexico paying for the wall. Presumably, the memo still sits there somewhere in the White House, untouched, ready for action, Plan A.

Act Two: No One Has Seen Them Made or Heard Them Made

Ira Glass

Act Two, "No One Has Seen Them Made or Heard Them Made."

Of all the walls all over the world that we learned about for today's program, this next one is the most mysterious-- a wall that may or may not even exist. Brian Reed looked into it.

Brian Reed

I read about this possible wall in a blog post. It's a travel blog by an Australian guy, and he tells the story of a bizarre tour he took in North Korea. The post is titled, "North Korea's Loch Ness Monster, The Concrete Wall."

For decades, the North Korean government has complained about the huge Concrete Wall that divides North and South Korea, a wall, it claims, that South Korea put up at the urging of the United States as a permanent barrier to reunification, a wall that's been a source of anger for the North Koreans for years. For them, it's a symbol of the duplicity and bad will of South Korea.

One peculiar thing about this wall, though, North Korea says it can only be seen from the northern side, that you can't see it from the south. It also doesn't show up on Google Earth or satellite images. But in North Korea, there's a place where tourists can go see it. That's where the blogger went.

According to the post, he arrived at a small bunker where a North Korean colonel delivers a whole lecture about the Concrete Wall. He stands there in uniform with a pointer stick-- there's a photo of this on the blog-- with a big mural behind him of the wall snaking along the border. Though, curiously, it's not a photograph of the wall. It's a painting.

The colonel runs through the wall's dimensions, which are listed on the mural, as well as geometric diagrams demonstrating the ingenious engineering that makes it only visible from the North. It's built into a hill, so from the South it just looks like green land. It's invisible. Which, the colonel explains, allows South Korea and the United States to claim that there isn't a wall between North and South Korea, which is exactly what those countries say.

And then, the colonel invites the tour group outside to see for themselves. The blogger is handed a pair of binoculars. The blogger writes that he half expects there to be a stencil of a wall taped on the lenses when he looked through. There isn't. But as he stares out from the observation deck into the DMZ, or Demilitarized Zone, the four kilometer-wide stretch of land that buffers North Korea from South, he does see something.

He includes a photo he took of it. Could this be what the North Koreans were talking about, he writes? Lean in and see what you make of it.

I did lean in. And honestly, I could not tell what the hell was going on in this photo. It's super blurry, taken from kilometers away on a hazy-looking day. There are shrubs and hills in the DMZ, and then, yeah, some type of brownish structure on top of the hills. But it's really hard to make out. It is like one of those Loch Ness photos.

This blog post confused me. Was there a wall between North and South Korea, or not? The news media seemed unequivocal on this question. The reports I read said the wall's not real. One headline from Reuters-- "North Korea asks South to tear down imaginary wall."

The blogger didn't want to be interviewed. So I ended up on the phone instead with a tour guide, named Simon Cockerell, who runs one of the most popular tour companies that takes people into North Korea. Simon says he's been in North Korea more than 160 times.

Simon Cockerell

So I've been even nearly to the Concrete Wall itself.

Brian Reed

You've been nearly to the Concrete Wall itself?

Simon Cockerell

Yes, that's right.

Brian Reed

So it is a wall. It is a thing. It exists. You're talking about it as if it exists.

Simon Cockerell

It, in some way, entirely does exist.

Brian Reed

Simon says he's done that whole tour the Australian blogger did.

Brian Reed

How many times have you seen this wall?

Simon Cockerell

I would have to guess, maybe 40 or 50 times.

Brian Reed

Did you ever, in any of those viewings, question whether what you were looking at was a wall?

Simon Cockerell

I honestly don't think I did. I mean, it's not a hologram. I mean, there's probably a semantic case to be made that it's not a wall because, on the southern side of it, it's a hill. And on the northern side of it, it's a wall. So it has the characteristics of a wall, if you're looking at it from the North, which after all is the only side from which you can see it.

Brian Reed

What are the characteristics of a wall, as you see them?

Simon Cockerell

It rises at a 90 degree angle from the ground, and it creates a barrier between where you are and the place on the other side of the wall.

Brian Reed

That's what exists in the DMZ.

Simon Cockerell

It's, at the very least, a wall-like object.

Brian Reed

There's a headline I want to read you from a journalist, Jon Herskovitz, who was based in Seoul for years and followed North Korea.

Simon Cockerell

I know Jon Herskovitz.

Brian Reed

Oh, you know Jon? OK, he wrote this article. I believe this was back in 2007, in Reuters. The headline is, "One of the greatest hindrances to tearing down the wall is that it doesn't exist."

Simon Cockerell

Mm-hm.

Brian Reed

What do you make of that headline?

Simon Cockerell

It's poetic. It sounds good. It's just not true.

Brian Reed

Really? So it's just straight up not true in your eyes.

Simon Cockerell

It's not really "in my eyes." It's sort of manifestly untrue. Yeah, Jon is 100% wrong about that.

Brian Reed

He said something to the effect of "Jon is 100% wrong."

Jon Herskovitz

Ugh.

Brian Reed

That "ugh" is Reuters journalist, reporter in Korea for five years, and author of the article with that headline, Jon Herskovitz. And he sticks to his guns-- no wall.

Brian Reed

How do you know there's no wall?

Jon Herskovitz

I've been to the border numerous times and also have crossed through the DMZ four times.

Brian Reed

And did you have to traverse a wall at any point?

Jon Herskovitz

No. I had to go through some razor wire and boom gates, but there was no wall to traverse.

Brian Reed

And when you looked left and right as you were crossing, did you see a wall anywhere?

Jon Herskovitz

I didn't see a wall. There is no wall.

Brian Reed

All that said, Jon may have been to the border a bunch of times, but he has not been to the observation point in the North that the blogger and Simon went to. He hasn't tried to view the wall from North Korea, which is convenient.

Brian Reed

So the fact that North Korea says you can't see the wall from the South, which is where you were looking for the wall--

Jon Herskovitz

Yes.

Brian Reed

That doesn't make you wonder if maybe there's a wall?

Jon Herskovitz

No, it doesn't, because they are very specific about what they have described. They describe it very distinctly as five to eight meters tall, 19 meters thick, and stretches from one end of the peninsula to the other.

Brian Reed

Jon says it'd be hard to miss a giant concrete barrier that's 62 feet thick, several stories high, running for more than 150 miles across the Korean peninsula. In the decades this wall's supposedly been around, someone would have bumped into it or glimpsed it on satellite. I told Jon I'd actually just talked to someone who says they've glimpsed it with their own eyes 40 or more times, the tour guide, Simon.

Jon Herskovitz

I'm guessing that he probably saw one of these tank barriers.

Brian Reed

Tank barriers, or anti-tank barriers-- Jon admits that these do exist in the DMZ between North and South Korea. South Korea's also copped to this. They're tall. They're big. You can't walk through them. They may even be made of concrete. But they do not come close to spanning the entire length of the peninsula, like North Korea claims.

Simon, the tour guide, admits he's only ever seen the wall from one spot. He doesn't know if it stretches the entire peninsula. He only knows what he knows, which is that claiming there's no wall, to him, is absurd.

Simon Cockerell

It's probably a tank barrier, as well. I mean, what's the purpose of a wall? Keep something out, or keep something in. And yeah, tanks are a thing. I think an anti-tank barrier can also be described as being a wall.

It's like going to the Great Wall of China, an anti-invading forces barrier. Hadrian's Wall is a wall, not just an anti-Scots barrier. I mean, what's the difference?

Brian Reed

It might seem silly to get into a semantic debate over the meaning of the word "wall," but that's where we are. When it comes to walls, apparently semantics matter. Jon pointed out to me that the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea is probably the most fortified border in the world.

There's razor wire fence on either side of it that does stretch across the entire peninsula. There are landmines everywhere inside. North and South Korea have about 2 million troops on either edge, with artillery and missiles and air forces at the ready.

This border does not need a concrete wall to stop people from crossing it or attacking, and yet the North Koreans felt the need to invent one anyway. It needed to be a wall. Even if it doesn't do much to actually stop people, even if it's imaginary, calling it a wall makes a difference.

Ira Glass

Brian Reed is the senior producer of our program and the host of the podcast S-Town.

Act Three: He Is All Pine and I Am Apple Orchard

Ira Glass

Act Three, "He Is All Pine, and I Am Apple Orchard."

Our next story takes place at the border between Pakistan and India. Nearly 2,000 miles, the border is heavily patrolled, lit at night, fenced in parts, a border between two countries that have gone to war four times-- 1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999.

It is still tense between India and Pakistan. Each has nuclear weapons. And there's only one road on that long, long border where you can cross from one country into the other, and that's in a town called Wagah, at a place they call the Berlin Wall of Asia.

Mariya Karimjee grew up in Pakistan. And the thing that she knew about Wagah was that they do this flag lowering ceremony there. It happens every day at sundown. Soldiers from both sides of the border do this elaborate, stylized, choreographed performance. Here's Mariya.

Mariya Karimjee

As a kid, I only knew the bare bones of what happened at Wagah. I knew there was some kind of marching, flags being lowered, a handshake. It's the handshake, the idea of the handshake, that got me.

An Indian soldier walks right up to the border and shakes a Pakistani soldier's hand. I loved it. It seemed so sweet. I'd always liked it whenever there was anything on TV showing our two countries getting along.

There'd be news reports of soldiers exchanging treats during religious holidays, standing across from one another with their comical wax mustaches raised in a smile. I saw a commercial in which border security officers stationed at Wagah shared a soda across the border. I liked the idea of these soldiers as friends, a border where everyone was chummy and spent a lot of time together.

I never actually went there as a kid. My family and I moved to Texas when I was 11, and I lived in the US on and off since then. Last year, my mother and I went to Wagah for the first time. It was not what I expected.

Crowd

[CHEERING]

Mariya Karimjee

I knew there'd be goosestepping. But if you've never seen a goosestep, nothing can really prepare you for a formation of tall Pakistani men, a dozen of them, in black military uniforms, handlebar mustaches, and turbans topped with large pleated bands swinging their legs up in unison without bending at the knee, and without missing a beat, quickly doing it again on the other foot. And again, it's a march. It's impressive.

[BOOTS CLICKING]

That's the crack of soldier's heels as they strike the ground. Then they switch to sky high kicks, their arms aggressively swinging to this exaggerated marching, looking a little like willful, frustrated toddlers. Someone on a PA leads the group in a series of chants.

Crowd

[SHOUTING] Pakistan, Pakistan. Pakistan is our home. Pakistan is our home.

Mariya Karimjee

The gates to the Indian side were closed. But over there, I know the Indian soldiers were doing the same choreography, same goosesteps, same high kicks. They also look nearly identical to Pakistan's soldiers-- military uniforms and shiny black boots with turban hats.

The two sides rehearse together. I like to picture that, them learning the steps, one Indian soldier asking a Pakistani soldier to go over the ending one more time, another showing off a new stretch he learned to loosen up his glutes, a frustrated stage manager counting angrily, "5, 6, 7, 8, [NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]."

The ceremony started in 1959 as an act of brotherhood and friendship between the two countries. And before visiting, I assumed that people came here to celebrate that. But in reality, the petty rivalries between the countries play out right in front of you.

Pakistan recruits their tallest, brawniest men, soldiers that are 6 feet or taller in a country where the average height for men is 5' 5". Pakistan pays their soldiers extra for staying in shape. India just doesn't seem to care that much. Their soldiers look scrawny by comparison.

At the same time, India seems like it can't resist showing off that it's the wealthier country. They built a majestic stadium that seats 15,000. It towers over everything, the whole ceremony, no matter which side you are sitting on. The Pakistan side, it's way smaller, rows of little plastic seats surrounded by concrete steps.

But what surprised me most at Wagah? There was an aggression I hadn't expected. It seemed like everyone was there to hate on India. The energy was frantic and hostile. People shook their fists at the Indians across from them.

Crowd

[CHANTING] Allah! Allah! Allah! Allah!

Mariya Karimjee

The crowd was intense, shouting things like, "Allah is great," and "long live Pakistan."

Crowd

[NON-ENGLISH SPEECH] Pakistan! [NON-ENGLISH SPEECH] Pakistan!

Mariya Karimjee

A few weeks ago, I returned to Wagah, and everyone I spoke to seemed to really, really hate India. The mom whose kids wanted ice cream, the teenager dressed in pink, the ex-military man and his wife, they told me they'd come out to show their national pride and to teach their kids about history. But they also went on in great detail with these crackpot conspiracy theories, like the Taliban are actually Indians, or that India continues to attack Pakistan across the Kashmir border, unprovoked, or that India was working stealthily to destabilize the government from the inside.

I felt dumb. I hadn't realized the extent of the hate and hostility that people still feel towards India. I told people, personally, I don't feel deeply about India. And I definitely don't think of India as an enemy. Almost everyone said that's because I'm too Western, and I didn't really know how it was in Pakistan. I couldn't possibly understand. Here at the border, it felt like my country, Pakistan, the underdog, was giving the middle finger to our neighboring country.

And maybe India was no better. A Pakistani friend who visited the India side of the ceremony said he cried when he realized just how much the Indians hated the Pakistanis. "Let's rape their sisters," he overheard an Indian spectator yelling. It's like if people from all over the United States and Mexico, full of anger, were to travel to the border between El Paso and Juarez to sit in some bleachers and face off, both shouting insults and screaming, "I'm better than you."

At the stadium, the moment comes when the gates open between the two sides, and we can finally see the Indian soldiers. The Pakistani and Indian troops stare each other down, pause, then high kick their legs up into the air, like a competition between manly Rockettes. The crowd howls.

In 2006, before some peace talks, India slightly lowered the height of their kicks. It was a gesture of goodwill, meant to show how sincere India was about improving relations between the two nuclear armed countries. They thought Pakistan would reciprocate. We did not.

Crowd

[CHEERING]

Mariya Karimjee

Finally, Pakistan and India lower their respective flags for the night. Bugles play.

[BUGLES PLAYING]

All the soldiers fall back, except for one Pakistani and one Indian. Face to face, feet apart, they each do a single, beautifully executed high kick in the other's face. And then, as promised, they shake hands, woodenly, before marching back to their troops. The ceremony is done.

Crowd

[CHEERING]

Mariya Karimjee

I will say, the handshake, I was glad to see it. I found it surprisingly moving in spite of my surroundings. I wondered if I was the only one who felt that way.

In the weeks since I went, I've thought a lot about how much emotion I saw pour out of people at Wagah. There's lots to be frustrated about in Pakistan. There's sectarian violence almost every single day. Politicians are nicknamed for how corrupt they are. Water is increasingly scarce. Police often don't follow up on crimes. The rich avoid paying taxes. You can't fight injustice through the legal system.

At Wagah, the single spot on the giant line that made Pakistan exist as a country, you can at least yell with some ferocity. Maybe it is a way to show your love for Pakistan. But I suspect a lot of the appeal is simply that you can yell.

Ira Glass

Mariya Karimjee.

Act Four: We Keep the Wall Between Us As We Go

Ira Glass

Act Four, "We Keep the Wall Between Us As We Go."

The very first official border wall between the United States and Mexico was actually just a fence in 1918 on the border between two cities with the same name, Nogales, Mexico, and Nogales, Arizona. Since then, the US has installed a much bigger fence-- thick, rust-colored steel rods. And every day at that spot at the border in Nogales, white buses from Homeland Security roll up full of people with deportation orders who are sent across the border into Mexico from the United States.

Lots of them are parents with kids who are still in the States. They then just take up residence right on the other side of the wall. There's no official estimate of how many. It's probably in the thousands. And one of the saddest premises for a community that you can imagine-- all these parents separated from their own children, who are US citizens, who stay behind, sometimes with the parents' approval and best wishes, sometimes not. Reporter Lizzie Presser was curious about how these parents of kids remake their family lives around all this-- one family, in particular.

Lizzie Presser

Many of the parents who get dropped off don't exactly decide to stay on the Mexican side of Nogales. It's more that they never make the decision to leave. They have no friends or family here. Their original hometowns in Mexico are hundreds of miles away. But Nogales is the closest they can be to their kids, who aren't that far away in places like Arizona, Nevada, or Utah.

Local officials told me that this population of deported parents is a new one. They started showing up under President Obama. Their numbers picked up even more under President Trump.

We hear about kids who get left behind in the States. But in Nogales, it's the parents who are orphaned. You can find these parents all over town. I met Emmanuel outside of a gym. He got deported two years ago.

Lizzie Presser

Why did you stick around?

Emmanuel

I'm here because I'm closer to my son. He's little, so he's two. He's barely walking. And I just don't want him to forget about me, you know?

Lizzie Presser

I then spotted this woman on the street wearing an Arizona Wildcats T-shirt and stopped her.

Lizzie Presser

I'm working on a story on parents who have been deported to Nogales.

Griselda Espinoza

Yeah, that's me, exactly me. So I got deported a year ago.

Lizzie Presser

This is Griselda Espinoza. Her kids are in Mesa, Arizona.

Lizzie Presser

How many kids do you have?

Griselda Espinoza

Three.

Lizzie Presser

And how old are they?

Griselda Espinoza

18, 16, and 6. It's hard, because I'm missing a lot of things.

Lizzie Presser

Are there are certain times of the day that you miss your kids most?

Griselda Espinoza

At night. At night, when I see their pictures. My son just won homecoming, and I wasn't there.

Lizzie Presser

She scrolls through her kids' Facebook pages every night before bed. I talked to another mom who said she sometimes spends hours on Google Earth tracing the streets in her old neighborhood in Phoenix.

I met parents all over the city. They work all day in factories and call centers and then come home to rooms they've decorated for their kids, who aren't there. One dad with a two-year-old still in Phoenix told me he installed a TV in his son's room, decked it out with Tonka trucks and Hot Wheels. When friends come over, he shuts the door to keep the room clean.

But when I asked him the last time his son came to visit, he said it was more than a year ago. Sometimes, it's a really long wait for kids to cross over from the States. The mom I spent the most time with is Gloria Marin.

Gloria Marin

You need to cook the chili colorado?

Lizzie Presser

This is her early one morning last fall. She talked to her kids on the phone, and it sounded like they were coming today. So Gloria was making her son Angel's favorite dish, chili colorado, a red sauce she mixed with beef and cactus.

I've known Gloria and her family for a year and gotten close to them. She used to live in Phoenix with her four kids. She raised them there as a single mom. Now she lives in a small room behind a friend's house. She keeps a couple extra beds propped up against her wall and got a chihuahua for her daughters. Like a lot of the other deported parents in town, she always wants to be ready for her kids.

Gloria has been in Nogales for more than five years. She's short with wavy black hair. She's quiet and kind of wistful when she talks. She wasn't expecting her kids until lunch, but she woke up at 5:00 AM to get ready. She wanted to look nice.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Gloria's saying, I showered. I got dressed. I brushed my hair. I cleaned the house. I made the food.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

And I wait for them.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

That's all.

Gloria and her kids spent all their time together when they were in Phoenix. They did Friday movie nights, took camping trips, sold toys together at a swap meet on the weekends to make extra money. And then one day back in 2010, Gloria got arrested while her kids were at school.

She'd been working as a housekeeper for a couple months when her boss got charged with running drop houses, places where undocumented immigrants spend the night after crossing the border. The prosecutors charged Gloria as an accomplice. She says she knew nothing about her boss's work, but she spent two years in prison. And then, since she wasn't documented, she was deported.

During that time, her kids lives started to unravel. The youngest was seven and the oldest 15. Her kids were split up and put into foster care. They could rarely talk to their mom or to each other.

Gloria spent her first year in Nogales trying to regain custody of her kids. But by the time she could convince Arizona's family court, only Gloria's youngest, who was 10, ended up joining her for a little. The others had been through hell, and they felt estranged from their mom.

It had been three years since they all lived together. Also, they didn't know Mexico, and they were scared to move there. They were US citizens whose lives were in Phoenix, three hours away.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Gloria told me, when I was young and my kids were little, I thought that I could never live without them. I never thought that one day they'd grow up, and I'd be far away from them.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

But you have to learn how to live like this.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

It's like a hope. It's the hope that any moment they'll say, Mom, I'm going over. And I'll be here waiting for them.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

I'm always just sitting around nervously, just waiting. I always await their visits thinking that, at any minute, they'll come.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

But they never really plan anything.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Today, they said they'd visit. But what Gloria didn't know was that they weren't planning on coming across the border to her house and eating her chili colorado. They only wanted to come as far as the wall. There's a small visitor's section where the wall is just a mesh fence where people from the two sides go to talk.

Yesi Marin

I want to stay on this side.

Lizzie Presser

This is Gloria's daughter, Yesi. She's 22, and she's bringing her two young children, one of whom has never met Gloria. And she just couldn't bring herself to tell her mom that she doesn't want to cross over into Mexico today.

Yesi Marin

No, if my mom hears that, she's going to be sad. She's going to think there's something wrong with her. I just make up excuses. I don't know what's wrong with me-- like excuse after excuse.

Lizzie Presser

Then why are you making up those excuses there?

Yesi Marin

I get super depressed not being able to be with her.

Lizzie Presser

She says it's really painful to see her mom. Gloria's house is a plywood shed, and she's working at a factory making $15 a day. Her health isn't great. She has diabetes.

Sometimes, she starts crying. And Yesi feels like there's nothing she can do to help her situation. It messes her up to see her mom that way.

Yesi Marin

I don't think she understands the effect of us seeing her like that. She always calls me and tells me like, why are you ignoring me? I'm your mother. You need to see me. You need to talk to me. I want to cook for you. She tells me all these things.

Lizzie Presser

Then what do you say?

Yesi Marin

I just tell her, oh, it's because I'm busy here. I've got stuff to do. But I don't do anything. I'm just here in my room.

Lizzie Presser

When was the last time you saw your mom?

Yesi Marin

I can't even remember. I think it was December of last year. Yeah, it's been that long.

Lizzie Presser

And that was at the wall. Yesi hasn't crossed over to visit her mother's house since 2014. It's not that she doesn't love her mom. They talk on the phone, text, send each other cute emojis.

But in the past, when Yesi's gone to see her mom, she's left her ID at home on purpose then told her mom it was an accident. That way, crossing wasn't an option. She could only meet Gloria at the wall and talk there. She wouldn't have to see her at her house. It just wasn't as intense. The wall is helpful for Yesi. It helps her keep some emotional distance.

Staying on the US side of the wall helps Yesi in another way. The last time she crossed over to visit Gloria in her home, four years ago, she'd only planned to visit for a few days. But she almost didn't come back. She ended up living there for four months with her daughter, who was just a toddler.

She hadn't felt that comfortable in years. She and Gloria talked about how Yesi could get a job on the US side of the border, commute there during the day, and then stay in Mexico with Gloria at night. And for months, Yesi let herself believe it was possible.

But then her real life caught up with her. She couldn't keep putting off school, her kids' dad, who was in Arizona. She had too many responsibilities. And ever since, seeing her mom just reminded her of what she couldn't have.

Lizzie Presser

You're nervous that if you go, you won't come back.

Yesi Marin

Yeah, because that's what I want. I just want to be with her. I guess I have no self-control. Ugh. That's why I don't like going over there.

Lizzie Presser

But have you ever thought about just saying to her, like, it's hard for me to come because I miss you too much?

Yesi Marin

How do you tell the person that you love the most in this world, I don't want to see you because I come home, and I'm not the same because of you? You don't want to tell her that.

Lizzie Presser

Her little brother, Angel, is also ambivalent about seeing their mom. And today, he plans to stay on the US side of the fence with Yesi.

Angel Marin

I get butterflies because I feel nervous. It's like I'm meeting a whole different person, even though I know her. I don't know. I just sometimes feel like I'm a stranger to her. And sometimes, she's a stranger to me.

Lizzie Presser

Angel's 18 now. He was 10 when Gloria was picked up. And in those eight years, Gloria has changed a lot. In prison, Gloria became really religious. Now she goes to mass three times each week, and she's always talking to Angel and Yesi about God, reading them passages from the Bible.

She used to stroll into school to pick them up in ripped Guess jeans and a big perm. At home, she'd blast Madonna and Michael Jackson while they cleaned the house together. Now she wears long dresses and "church lady" shoes. She's reserved.

Angel's kind of a goof, and he used to crack his mom up all the time. But now, he says, she's lost her sense of humor. He feels like he can't be himself around her.

Angel Marin

I'll make fun of people, just be like, yo, that guy gots a bald head. You can see your future. And it's like a magic ball. And she'll be like, don't make fun of that person, you know? They have issues too.

I'll be like, Mom, I'm just trying to make you laugh, but OK. If you're just going to continue to be like that with me, then why should we even speak? Because I don't want to feel that vibe with my own mother.

Lizzie Presser

Do you feel like she used to appreciate this part of you?

Angel Marin

I think so, yeah, shoot.

Lizzie Presser

Angel and Yesi both can't let go of the way their mom used to be back in Phoenix. Yesi wants her to act more like a mom, to fake that she's happy even when she's not, to tell her what to do.

Of course, they have practical reasons for not visiting. They don't have much money for bus tickets. Yesi's kids need her attention. It's easy to blame it on that stuff and not talk about the rest of it, though it's hard not to feel guilty.

Angel Marin

Sometimes, I feel like my mom feels that we don't love her.

Lizzie Presser

Do you feel like your love for your mom now is the same as it was before she left?

Angel Marin

I really don't know what it is right now. [LAUGHS] When my mom, she tells me she loves me, I'll tell her, I love you too, Mom.

Lizzie Presser

And what do you feel?

Angel Marin

Nothing.

Lizzie Presser

Is that scary?

Angel Marin

No, it's just a feeling that you feel, like when you're just too deep into something that you just can't get out of, or you feel you can't get out of.

Lizzie Presser

Angel's not completely disconnected from Gloria though. He's discovered that she has a very specific physical effect on him that no one else has. After Gloria was arrested, Angel stopped being able to sleep through the night. But when he visited her at her home in Nogales for the first time, Gloria lay down next to him. At the time, he was just 14.

Angel Marin

I instantly fell asleep because she was rubbing my head. I just knocked out quick.

Lizzie Presser

Had you not had that since she'd been arrested?

Angel Marin

Yeah. That was like the best, decent sleep. Like, I would compare it to the last time I was like in the fetus, bro, like just chilling, just going-- just sleeping, you know? I had no thoughts, no negative thoughts. I didn't have to worry about bills, no nothing.

Lizzie Presser

Sounds like very good sleep to me.

Do you ask them to visit more often?

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Gloria told me, yes, but I don't know.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Maybe because of time and money, I don't know.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

They can't come so much. I don't know.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

So I never thought that this would happen, that they'd make the decision to not come.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Before, I used to get angry because they didn't come. And I used to ask myself why, ask myself if they'd lost their love for their mom and all that.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

But now, I just want them to feel good so that they want to come again.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

So these days, that's Gloria's entire strategy. She tries to play it cool when she's on the phone with them. She doesn't want to sound needy or talk about how hard things are for her.

In the morning, back in Phoenix, Yesi put on full makeup. Brisa, the youngest kid, braided Angel's hair. The three of them packed into the car around 7:00 AM with Yesi's kids and headed south to stand on the Arizona side of the border and talk to their mom through a fence.

In Nogales, Gloria finished cooking and then sat on her bed, watching the clock, still unaware that her kids weren't planning to cross over. When it hit 10:00 AM, Gloria left her house, got in her car, and started driving to the border to pick them up, 10 minutes away.

[PHONE RINGING]

Suddenly, her cell phone rang.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

It was her kids.

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Gloria's saying, are you guys coming?

Gloria Marin

[SPEAKING SPANISH]

Lizzie Presser

Wait, you're there? I'm on my way.

Gloria Marin

OK, mijo, I love you.

Lizzie Presser

Her kids had all crossed. I don't think it was because I was with them recording. They'd had a massive change of heart. Brisa, the youngest, had been telling her siblings that Gloria was doing fine, and they needed to chill out and stop making such a big deal out of visiting her house.

And so when they got to the border, the siblings didn't talk about it. Nobody said anything. Angel looked down and saw his feet walking across the border. They pushed through a metal gate. Suddenly, they were in Mexico. Gloria pulled up and honked.

Lizzie Presser

Yesi, it's your first time here in three years.

Yesi Marin

I know. It's been a while.

Lizzie Presser

Yesi went to hug her. She told her mom that her hair smelled good. Everyone kissed each other and piled into the car.

At Gloria's house, the kids immediately sat down to start eating. They only had an hour. Angel had to get back to Phoenix for work that night.

For all their talk about their hang ups with their mom, they got casual really fast. Yesi's bodysuit was bothering her, so she unsnapped it and let the flaps hang loose. Angel was trying to learn how to say "burp" in Spanish.

Angel Marin

Is it "eructa" or "erupta?"

Gloria Marin

Eructa.

Lizzie Presser

Gloria wasn't eating. She was just watching them. She had this dreamy smile on her face. This was the first time they'd all sat around a table together since 2010.

After lunch, they all climbed into Gloria's bed, insisting they had food comas. But really, they just wanted an excuse to cuddle with their mom. Angel curled up. He's about 5 feet, 90 pounds. He'd insisted on wearing a baggy sweatshirt that day so he didn't look too skinny. Gloria started rubbing his head. It was like a magic trick.

Angel Marin

When my mom rubs my head and I'm sleeping, it's already over.

Lizzie Presser

Angel closed his eyes, and then it was time to leave. Yesi and her kids stayed behind with Gloria, but just for three extra days this time. They talked again about living together in Mexico.

Yesi told her she'd move down there in a month or so. She'd buy Gloria a plot of land with a small house, just big enough for the whole family. Yesi told me it made them both happy, just saying all those things, even though she knew and her mom knew that it wasn't going to happen. And for the first time, that was OK.

Ira Glass

Lizzie Presser. To help report this story, Lizzie got a grant from the International Women's Media Foundation as an Adelante Fellow. She was also supported by the Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute

[MUSIC - "WHEN THE WALLS CAME DOWN" BY THE CALL]

(SINGING) Well, they blew the horns, and the walls came down. They'd all been warned, and the walls came down. They stood there laughing. They're not laughing anymore. The walls came down.

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program was produced today by David Kestenbaum and Louise Sullivan. The people who put our show together includes Elna Baker, Elise Bergerson, Ben Calhoun, Dana Chivvis, Sean Cole, Stephanie Foo, Michelle Harris, Kimberly Henderson, Miki Meek, Alvin Melathe, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp, Christopher Swetala, Matt Tierney, and Diane Wu. Our senior producer is Brian Reed. Our managing editor is Susan Burton. Production help from Anna Martin and Stone Nelson.

Special thanks today to Robert Frost, to California Sunday Magazine, The Kino Border Initiative, Carmen Noriega, Catalina Maria Johnston, Vicky Cosstick, Peter Curran, Mark Gordon, Zeynep Bilginsoy, Matt Alesevich, Zach Campbell, James Hathaway, Rebecca Hamlin, Jesus Blasco de Avellaneda, Nick Fountain, Nate Rott, Charles Maynes, Frankie Quinn, Brahim B. Ali. Interpreting today by Daniel Sherr.

Our website, where this week we have this incredible interactive map where you can fly around to see all the walls in today's stories all over the globe, created by International Mapping. See that at thisamericanlife.org. This American Life is delivered to public radio station by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange.

Thanks, as always, to our program's co-founder, Mr. Torey Malatia. You know, he just showed us our new office plan. We are all moving into cubicles-- very, very tiny cubicles. He likes them small.

Angel Marin

I would compare it to the last time I was in the fetus, bro, like just chilling.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

[MUSIC - "WHEN THE WALLS CAME DOWN" BY THE CALL]