562: The Problem We All Live With - Part One

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Prologue

Ira Glass

Nikole Hannah Jones is an investigative reporter, these days at The New York Times. We've had her here on This American Life before too. But her first big reporting job was back in 2003. She was reporting on the schools in Durham, North Carolina. And like most places, there were good schools and there were bad schools. And at the time, it was the heyday of No Child Left Behind. Durham was working really hard to improve the bad schools.

Nikole Hannah Jones

And I would go to schools, and they would just always be trying these new things that actually sounded like they might work. They would do things like, "We'll put a great magnet program here. Or we are going to really focus on literacy. We're going to start an early college high school, which kids would earn college credit in high school. We're going to improve teacher quality. We're going to replace the principal. More testing."

They're always talking really about the same things. I mean, you could take these conversations and go from district to district to district, and you will always hear the same things.

Ira Glass

And what she noticed was that it never worked. I mean, like, never. The bad schools never caught up to the good schools. And the bad schools were mostly black and Latino, the good schools mostly white. And sure, there might be a principal here or a charter school there who might do a good job improving student scores. But even there, they were just improving the students' scores. The minority kids in their programs were still not performing on par with white kids. They hadn't closed the achievement gap between black kids and white kids.

Nikole Hannah Jones

And my question is, all of these different ways that we say we're going to address this issue aren't working. So what actually works? And that's what I really began to look at. And I find this one thing that really worked, that cut the achievement gap between black and white students by half.

Ira Glass

By half?

Nikole Hannah Jones

By half. But it's the one thing that we are not really talking about, and that very few places are doing anymore.

Ira Glass

That thing that is so effective but never discussed? That's not one of the tools that educators reach for normally? Can you guess?

Nikole Hannah Jones

Integration.

Ira Glass

You mean just integrated schools? Just getting black kids and white kids together in the same schools?

Nikole Hannah Jones

Yes.

Ira Glass

Old fashioned, Brown versus Board of Education, 1954 technology, little kids on buses?

Nikole Hannah Jones

That's right. Actually, what the statistics show is that between 1971, which is where the nation really started doing massive desegregation, and 1988, which was the peak of integration in the United States, 1988 was the peak.

Ira Glass

School integration.

Nikole Hannah Jones

School integration, yes. Well, the data shows that at the start of real desegregation, the achievement gap between black and white students was about 40 points.

Ira Glass

In other words, on standardized reading tests in 1971, black 13 year olds tested 39 points worse than white kids. That dropped to just 18 points by 1988 at the height of desegregation. The improvement in math scores was close to that, though not quite as good. And these scores are not just the scores of the specific kids who got bused into white schools. That is the overall score for the entire country. That's all black children in America. Halved in just 17 years.

When I asked Nikole if that was fast, she was all like, "Well, black people first arrived on this continent as slaves in 1619. So it was 352 years to create the problem. So yeah, another 17 to cut that school achievement gap in half? Pretty fast."

Nikole Hannah Jones

And so if you picture that out if we had kept going, when we had cut it by half, I don't know that we would have eliminated it totally, because there's a long history here. But you could see where we would be. We would have been so close to eliminating it.

Ira Glass

Nikole, why does it work?

Nikole Hannah Jones

I think it's important to point out that it is not that something magical happens when black kids sit in a classroom next to white kids. It's not that suddenly a switch turns on and they get intelligence or wanting the desire to learn when they're with white kids. What integration does is it gets black kids in the same facilities as white kids, and therefore it gets them access to the same things that those kids get-- quality teachers and quality instruction.

Ira Glass

The US Department of Education put out data in 2014 showing that black and Latino kids in segregated schools have the least qualified teachers, the least experienced teachers. They also get the worst course offerings, the least access to AP and upper level courses, the worst facilities.

The other thing about most segregated black schools, Nikole says, is that they have high concentrations of children who grew up in poverty. Those kids have greater educational needs. They're more stressed out. They have a bunch of disadvantages. And when you put a lot of kids like that together in one classroom, studies show, it doesn't go well.

Nikole Hannah Jones

If you're surrounded by a bunch of kids who are all behind, you stay behind. But if you're in a classroom that has some kids behind and some kids advanced, the kids who are behind tend to catch up. These kids in these classes in schools of concentrated poverty don't have that. They don't have that effect of kids who can help boost them. Everyone's behind.

And then they're getting the worst teacher. So it's not even like they're getting the same quality teachers as kids who are advanced. They're getting worse teachers. When you combine those two things, it is almost impossible to undo that harm. You have to break that up.

Ira Glass

This is why after years of studying this, Nikole thinks segregated schools full of poor kids are probably never going to catch up to other schools. The job is simply too hard. But integration-- before I talked to Nikole about this, I had this vague sense about integration-- maybe you had this too-- that we tried that. It didn't go so well. Which Nikole has heard before.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Yeah, that's a pretty common thought. People say, "Well, we tried to force it and it just didn't work out." And typically what people are thinking of are places like Boston, where busing was used and where it was violent and ugly and white people just left and didn't want to deal with it.

Ira Glass

White people fled the school systems and basically they resegregated the school systems by fleeing.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Right. And I should be clear. I'm a product of busing myself. And I rode a bus two hours a day.

Ira Glass

Where did you grow up?

Nikole Hannah Jones

I grew up in Waterloo, Iowa. And yes, there are black people in Iowa. I get that question all the time.

Ira Glass

Nikole says that her parents sent her and her sister to a school across town, which was all white, except for five black kids, which included the two of them.

Nikole Hannah Jones

And at the time, I didn't realize that it was a bussing or integration program. My parents told me to get on the bus and go to school, and I went where the bus took me.

Ira Glass

Right.

Nikole Hannah Jones

But I didn't really understand until I started covering education that we were part of a desegregation program. And one of the things that has been challenging as I write these stories is knowing that bussing for me was actually very hard. We had to get up really early, but also we were being taken out of our community into someone else's community, where not only was it a white community but it was a wealthy community, and I was coming from a very black working class community.

And so socially, it was very difficult. You just never felt like you belonged or it was your school. I had friends and I could go to their house, but they couldn't come to mine. And there was this time when I was in middle school, there was a pool on our side of town. And then there was another pool on the other side of town. And we used to always go to the pool on the white side of town. And one day, I was like, "Hey, guys, why don't you come to my house and we can go to the pool on my side of town?"

And all my white friends were like, "Yeah, we're going to do it." And then that morning, one by one, they called and said they couldn't come. And to this day, that devastates me. I'll never forget how that felt. Because I knew why. I knew why they did that.

Ira Glass

What did they say?

Nikole Hannah Jones

They just said, "Oh, our mom said we can't come, but you can come over here." Every last one of them. I mean, that's the thing. We somehow want this to have been easy and we gave up really fast. I mean, there was really one generation of school desegregation.

There's a lot of data that shows that black students going through court-ordered integration, it changed their whole lives. They were less likely to be poor. They were less likely to have health problems. They lived longer. And the opposite is true for black kids who remained in segregated schools.

Ira Glass

It's so funny the way you say that-- "Well, how do we know that integration works?" You're saying well, you know from the evidence of your own life.

Nikole Hannah Jones

I know from my own life, and now being able to look at the longitudinal data on it, realizing that, yes, I am living the life that that data says you live when you have the opportunity to go to an integrated school.

Ira Glass

So integration works. And yet, we do not discuss it usually as the logical way to fix schools.

Nikole Hannah Jones

And I think I'm so obsessed with this because we have this thing that we know works, that the data shows works, that we know is best for kids. And we will not talk about it. And it's not even on the table.

Ira Glass

And so today, we thought we would put it on the table and talk about it. From WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Today, after years where very few communities were launching new desegregation programs, Nikole found a place that just three years ago, unintentionally, started school desegregation. Seriously, nobody in charge planned this. A school system got integration and Nikole got to see what happens to the kids, what happens with the parents, which is not pretty, and what happens with the politics in modern day America, when school desegregation shows up uninvited to the table by any of the usual people in charge. Stay with us.

Act One: The Problem We All Live With PART ONE

Ira Glass

And with that, I will turn things over to Nikole. A quick heads up, somebody uses a racial slur in this first part of the story.

Nikole Hannah Jones

I stumbled on this place by accident. I was watching the coverage of Michael Brown almost a year ago, like the rest of America. There was one moment that I could not get out of my head. It's news footage of his mother, Leslie Mcspadden, right after he was killed.

Leslie McSpadden

This was wrong, and that was cold-hearted.

Onlookers

It was. It was! No justice, no peace!

Nikole Hannah Jones

She's standing in a crowd of onlookers, a few feet from where her son was shot down, where he would lie face down on the concrete for four hours, dead. And this is what she says.

Leslie McSpadden

You took my son away from me. You know how hard it was for me to get him to stay in school and graduate? You know how many black men graduate? Not many!

Nikole Hannah Jones

I watched this over and over. A police officer has just killed her oldest child. It has to be the worst moment of her life, but of all the ways she could have expressed her grief and outrage, this is what was on her mind-- school, getting her son through school.

Michael Brown became a national symbol of the police violence against black youth, but when I looked into his education, I realized he's also a symbol of something else, something much more common. Most black kids will not be shot by the police but many of them will go to a school like Michael Brown's.

It took me all of five minutes on the internet to find out that the school district he attended is almost completely black, almost completely poor, and failing badly. The district is called Normandy. It's made up of one high school, the one that Michael Brown attended, a middle school, and five elementary schools. It's in a town also called Normandy that borders on Ferguson.

Each year, the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education puts out a report that shows how each of its 520 school districts is doing. It's a numeric snapshot of the type of education students are receiving. Districts get points for academic achievement, for how many students graduate, for how well they're prepared for college.

In 2014, Michael Brown's senior year, here's how the Normandy School District was performing. Points for academic achievement in English-- 0, math-- 0, social studies-- 0, science-- 0, points for college placement-- 0. It seems impossible, but in 11 of 13 measures, the district didn't earn a single point. 10 out of 140 points, that was its score. It's like how they say you get points on the SAT just for writing your name. It's like they got 10 points just for existing. Normandy is the worst district in the state of Missouri.

Maybe Michael Brown's mom knew these scores. Or maybe she just knew her son's school didn't graduate about half of its black boys. I don't know. I reached out to her several times and she didn't want to talk. But in the Normandy district, mothers who are worried about the quality of the schools aren't hard to find.

Over the last couple of months, I spent a lot of time with one of them, a Normandy mother named Nedra Martin. And it was through her that I learned the story of something that happened in this district, something that almost never happens anymore. Nedra grew up in Normandy and works in human resources. Her daughter, Mah'Ria, is a star student. Still, Nedra found herself worrying about Mah'Ria's education all the time.

Nedra Martin

Mah'Ria, to be honest with you, she wasn't having a problem. I'm just going to say, she's an awesome child, OK? I love her.

Nikole Hannah Jones

When you ask them questions, Nedra, Mah'Ria, their eyes fix on each other. I've got a daughter and I kept wondering what magic parenting spell Nedra has cast to get her teenage daughter to like her so much. Nedra's older daughter went to Normandy too. She almost didn't graduate on time because the school lost track of her credits.

By the time Mah'Ria got to middle school, little things started happening that begin to worry Nedra even more. Mah'Ria usually brought home As, but when she got a C, Nedra asked the teacher why she had not been notified. The teacher told her that she had too many kids in her class to call all their parents. Nedra said teachers did not seem to care. Classes were dumbed down and often unorganized and unruly. And even things that should have been good news turned to bad news.

In seventh grade, Mah'Ria was invited to a special breakfast. It was to celebrate kids who made the honor roll. They began calling kids up, one by one, to get their certificates.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

I'm like, OK, I'm next. And then another name gets called. And I had to remind myself A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P. And I'm like, my name is Pruitt-Martin. You guys skipped Pruitt.

Nikole Hannah Jones

They never called her name. When Mah'Ria asked the school counselor about it, the counselor told Mah'Ria maybe she wasn't supposed to be there. Nedra, who had taken off of work to come, was watching from the side.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

She looked at me and I looked at her. Then I was like, "Something's wrong. Something is wrong." I almost started crying, really. Because I felt not embarrassed but really, really disappointed.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Mah'Ria had the invitation to the breakfast in her bag. She'd brought it just in case something like this happened. Think about that. This is a 12 year old girl who is so used to the school screwing things up that she knew enough to bring proof. It was a small thing, but for Nedra and Mah'Ria, it was the last straw.

Nedra knew that the district had been performing poorly for years. In fact, it had been on probation for 15 years. Schools in Missouri get accredited by the state. Almost every district is accredited. But if you're doing really bad, you get put on notice. That's called provisional accreditation. That's supposed to be like a warning. But Normandy had provisional accreditation for 15 years. That means there are entire classes of students, nearly all of them black, who came in as kindergartners and graduated 12 years later without ever having attended a school that met state standards.

In the St. Louis area, nearly one in two black children attend schools in districts that performed so poorly the state has stripped them of full accreditation. Only 1 in 25 white children are in a district like that. That's one in two black kids, 1 in 25 white kids.

Nedra Decided she had to get Mah'Ria out of Normandy. She made a list of nearby school districts and private schools. Then she turned her car into a mobile situation room. The mission-- get Mah'Ria into a better school.

Nedra Martin

Obviously, when I'm at work these offices are open. When I get off, they're closed. So what I would do is take later lunches on my job, go to my car, sit in my car after I've written down telephone numbers and names the night before, and I would spend my whole lunch hour calling these offices.

Nikole Hannah Jones

The nearby districts told Nedra they would enroll Mah'Ria, but since she lived outside of their boundaries Nedra would have to pay tuition, upwards of $15,000 a year. She couldn't afford that.

Nedra Martin

If I would be required to pay for her get a public education then I might as well try to send her to a private school.

Nikole Hannah Jones

She checked into those, but even with financial aid, she couldn't afford private school either.

Nedra Martin

I was at a point of desperation. I was literally desperate to just pull my daughter out of a district that I felt failed me and my children. I was at a point of desperation. We had to do better.

Nikole Hannah Jones

In most of the thousands of poor, segregated schools in America, that would be it. Your zip code is the anchor that traps you. That would have been it for Nedra too, if it weren't for what happened next.

Newscaster

New tonight, a major blow to a school district in the metro area. The Missouri State Board of Education is pulling accreditation from the Normandy School District.

Nikole Hannah Jones

In January of 2013, just a few months after that breakfast, Normandy lost its accreditation from the state. No one really explained why they'd lost it after all this time. Remember, they'd been on probation for 15 years. The school stayed open, but this rare event triggered a little known Missouri law called the transfer law. The transfer law gives students in unaccredited districts the right to transfer to a nearby accredited one for free. Any student in Normandy was now allowed out.

Nedra Martin

I was elated. I was just so excited, like God had of truly answered my prayers. Because that sense of desperation, it was a burden. It was honestly a weight lifted off my shoulders.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

She told me and I was like, "What? What does that mean?" And she was like, "That means you get to go to a different school district." I was like, "What? Say that again? Really?" I so happy.

Nedra Martin

I was just excited. I think Mah'Ria and I got together and just did a swing dance of some kind.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Do you remember that conversation at home?

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

We were so happy.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Under the law, while Normandy students can enroll in any nearby accredited district, Normandy has to provide transportation to just one. Normandy officials chose a district called Francis Howell. Francis Howell was 85% white. It sits across a river in another county, roughly 30 miles away from Normandy. One of the best districts in Missouri was just five miles away.

It would have been very easy for Normandy students to get there. Why not send them there? Well, if you don't want students to leave your district, one way to keep them is to make leaving inconvenient. Make them ride a long distance to school every day. Though Normandy officials deny that's why they chose Francis Howell.

Douglas Carr was a teacher in the Normandy district. He says when they first heard about the transfer option on the news, a lot of the Normandy teachers didn't expect many kids would take it.

Douglas Carr

Well, honestly, I thought, "Well, how many parents are going to want to get their kids up early and send them to a school 30 miles down the highway?" That, to me, was a little extreme.

Nikole Hannah Jones

1,000. That's how many kids wanted to do that. That fall, fully one quarter of Normandy students chose the evacuation plan the law created, even though many of them would have to get on a bus at 5:00 in the morning and travel a good 30 miles away.

The word "integration" does not appear in Missouri's transfer law. When the law was passed, no one thought an entire district would lose accreditation. Integration was not the law's intent. But the Normandy kids are almost all black, the Francis Howell kids nearly all white. And that is how Missouri accidentally launched a school integration plan in what was an unfashionably late year for such a thing-- 2013.

Though Normandy chose to provide free transportation to the Francis Howell school district, Francis Howell wasn't part of that decision. By law, they had no say in the matter. So a week after the announcement that Normandy would bus kids to Francis Howell, officials there held a town meeting to talk about it. Nedra and Mah'Ria decided to go.

Nedra Martin

That night, it was a traffic jam getting there. I mean, because it was packed. To get up in this town hall meeting, you would think it was a celebrity in town or something. That's how crowded it was.

Nikole Hannah Jones

They parked and walked in. Mah'Ria looked around, surveying the gym-- a sea of 3,000 mostly white faces.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

Bleachers on each side, those were filled. Then you had chairs that were in two columns, and people were filling up those seats to say something in the mic.

Rebecca

Hello, my name is Rebecca and I have children in the district. And I'm concerned.

Nikole Hannah Jones

St. Louis Public Radio recorded the meeting. One by one, parents tick off concerns. There are questions about class sizes, money, how this will affect special ed, fire safety.

Woman

Once Normandy comes in here, will that lower our accreditation?

[APPLAUSE]

Nikole Hannah Jones

A woman says she was an education professor and warned Francis Howell officials not to be naive about the type of students they'd be receiving.

Woman

So I'm hoping that their discipline records come with them, like their health records come with them.

[APPLAUSE]

Nikole Hannah Jones

The elected school board was sitting at tables in the front of the gym. Now and then, one of them jumped in.

Woman

I just want to remind everybody that this timeline, nor this solution, are solutions that Francis Howell would have chosen either. We're doing the best that we can. It hasn't even been two weeks ago that we've been notified. We did find out yesterday that those student scores will become our scores.

[GROANING]

Nikole Hannah Jones

One mother asked why residents did not get to vote on letting in Normandy kids like they vote on public transportation.

Woman

Years ago, when the MetroLink was being very popular, St. Charles County put to a vote whether or not we wanted the MetroLink to come across into our community. And we said no. And the reason we said no is because we don't want the different areas [INAUDIBLE] coming across on our side of the bridge, bringing with it everything that we're fighting today against.

Nikole Hannah Jones

A mother named Beth Cirami approaches the microphone.

Beth Cirami

This is what I want to know from you. In one month, I send my three small children to you, and I want to know is there going to be metal detectors?

[APPLAUSE]

Because I want to be clear. I'm no expert. I'm not you guys. I don't have an accreditation. But I've read. I've read, and I've read, and I've read. So we're not talking about the Normandy School District losing their accreditation because of their buildings, or their structures, or their teachers. We are talking about violent behavior that is coming in with my first-grader, my third-grader, and my middle schooler that I'm very worried about. And I want to know. You have no choice, like me. I want to know where the metal detectors are going to be, and I want to know whether your drug sniffing dogs are going to be. And I want-- this is what I want. I want the same security that Normandy gets when they walk through their school doors, and I want it here.

[CHEERING]

And I want that security before my children walk into Francis Howell. Because I shopped for a school district. I deserve to not have to worry about my children getting stabbed, or taking a drug, or getting robbed. Because that's the issue. I don't care about the taxes.

Nikole Hannah Jones

To be clear, Normandy did not lose its accreditation because of violence. It's easy to judge these parents, but I think part of what makes this scene so startling is that we rarely fight these battles anymore. The reaction to large numbers of black children moving into white schools would probably sound no different in New York, or Chicago, or Boston. It's just that, in most of the country, no one is even trying. These parents don't want to try either. So one of them offered a helpful solution.

Man

Yeah, you're absolutely right. We have to do this. We have to follow the laws. We don't have to like it, and we don't have to make it easy. Has anyone considered changing our school start times? Moving start times up 20 minutes, maybe 40 minutes? Making it a little less appealing?

[CHEERING]

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

I knew that there would be negative opinions but not that negative. I didn't think it would be like that.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Mah'Ria was watching it all on the monitors in an overflow room. At a certain point, she grabbed her mom's hand and told her she wanted to speak at the mic.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

Because I felt that I needed to represent what if your kid was in a Normandy high school and they were just offered this opportunity, and other parents are saying "We don't want you here." How are you going to feel? Your kid's going to cry because parents are saying how awful your kid is, when really they're being put in a box because they're not like that. We're just stuck there because we're not open to the opportunities. And now we're open to them, and now you want to be all mean, talking about how you're afraid of how big the class is going to be, the violence in the schools. And so-- [SIGHS]

Nikole Hannah Jones

That's what she planned to say.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

So I had to walk out, go to the big gym. And we were standing by the door, me and my mom were walking towards the [INAUDIBLE] and I had hesitated. I didn't even get halfway to the microphone because of what the parents were saying. I stopped the second to last row of chairs, because I did not want to say anything anymore.

And then this lady, I don't remember who she was. She was like, "I'll hold your hand." Because I started getting a little teary eyed. But I just couldn't do it.

Nikole Hannah Jones

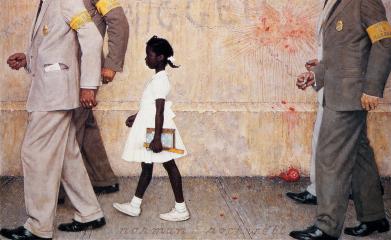

Nedra saw her daughter freeze. She said she thought about Ruby Bridges, the first black child to attend an all white elementary school in the South. She's the little girl guarded by US marshals in the famous Norman Rockwell painting called The Problem We All Live With.

Nedra Martin

We're still dealing with that today. We're still dealing with that today. I kept telling myself, as if I was talking to those parents who were not embracing this decision, my child may be the doctor that saves your life one day. My child may be the lawyer that defends your child one day. How dare you.

Nikole Hannah Jones

The conversation in the gym is taking place in one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country. Of course, there are poor white children in the St. Louis area, but they live in mostly middle class areas, so they aren't attending schools as terrible as Normandy's. In St. Louis, poor white children are twice as likely to go to good schools than black children of all incomes. But race barely comes up that night, except when white parents insist it is not the issue.

Woman

We have both-- my husband and I both have worked and lived in underprivileged areas in our jobs. This is not a race issue. And I just want to say to-- if she's even still here-- the first woman who came up here and cried that it was a race issue, I'm sorry, that's her prejudice calling me a racist because my skin is white and I'm concerned about my children's education and safety.

[CHEERING]

This is not a race issue. This is a commitment to education issue.

Nikole Hannah Jones

The year the Supreme Court handed down the Brown versus Board of Education ruling banning school segregation, St. Louis was the second largest segregated school district in the country. It was 1954. After a lot of resistance, many school districts went through desegregation battles, but St. Louis came to it extraordinarily late.

Real desegregation didn't get going in St. Louis until the 1980s. Even then, it was only because black families sued. But by that point, there were hardly any white kids left to integrate with. That's why a federal judge ordered white suburban schools to take thousands of black students from the city to the suburbs. He did that because he said St. Louis's white suburbs shared the blame for the segregation in the city schools.

This was 30 years, a full generation after Brown. And the students who went through that, some of them, anyway, grew up to be the parents in the Francis Howell gym. So when they got to the mic, they aren't just talking about the current situation. A lot of what they're saying is a referendum on what happened to them when they were kids. For instance, here's how Beth Cirami, the mother of three who was asking for metal detectors, began her remarks.

Beth Cirami

Being from Jennings, I've watched the dismantling of an award-winning school district. I've watched it. I went to Catholic school because I had to. Not because I wanted to, but because I had to. So I know the routine.

Nikole Hannah Jones

This is how white parents in the gym frame the story, that schools failed in the past because black children were forced in. That's what went wrong, not the other part of the equation, that white families chose to leave. But the few black parents who stand up to speak have a remarkably different memory of the exact same period of time.

Woman

I'm a native of St. Louisan, was part of the deseg program. Very great opportunity for me. I was a great student. Worked out for me. And my question is that, what are we doing as far as helping with the transition of these students coming into Normandy?

Nikole Hannah Jones

A generation of black St. Louis residents, tens of thousands of them, remember the St. Louis desegregation program just as she does, as a great opportunity. They will be the first to tell you it was hard, but also that it was necessary. And for the most part, it worked. In the schools where white families chose to stay, test scores for black transfer students rose. They were more likely to graduate and to go to college. After years of resistance, St. Louis had created the largest and most successful metro-wide desegregation program in the country.

But from the moment it started, state officials worked to kill it. In 1999, just 16 years after real desegregation came to St. Louis, the desegregation order ended. Just a much smaller voluntary desegregation program remains. Michael Brown's mother, by the way, was part of that brief 16 year window. She was one of the students who was bussed out of St. Louis when she was a kid. But her own son, Michael, went to one of the most segregated districts in the state.

This is what happened in cities all over. With Brown versus Board of Education, we as a nation decided that segregated schooling violated the constitutional rights of black children. We promised that we would fix this wrong. And when it proved difficult, as we knew it would be, we said integration failed instead of the truth, which is that it was working but we decided it wasn't worth the trouble.

Beth Cirami

I don't care about everything else that falls by the wayside, because it will, two to three years when we all move out of the district. I care about--

Nikole Hannah Jones

It's not an empty threat. "If you let those children in, we will leave-- again."

Man

And let me assure you. I personally know a family in the Fox School District that was shopping for houses in our school district. They were negotiating on a home. And when this came on the news, they ended negotiations. So--

[APPLAUSE]

Nikole Hannah Jones

On the ride home, Mah'Ria felt intimidated, but she was determined to go to Francis Howell.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

I actually kept telling myself, "The parents aren't the one that's going to the schools. It's the kids. Keep reminding yourself that."

Nikole Hannah Jones

And so, though she didn't think about it this way, that fall, Mah'Ria joined an old American tradition-- black children headed on buses to heavily white schools that had been forced by the courts to take them.

She hadn't ridden the school bus since she was little. On the first day of school, she rose to catch the bus at 5:45 AM. She found a seat, rode the 30 miles to Francis Howell, and as the bus pulled into the school parking lot, she peered nervously through the window. And what she saw surprised her.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

It was great. Because when I got there, they had their little cheerleading squad cheering for us when we walked through the door-- "Welcome to Francis Howell," cheers like that. I'm not a cheerleader, so I don't know exactly what they were saying, but just cheering, doing high kicks and everything like that. It was great. I loved it.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Francis Howell administrators would not talk to me, but best as I can tell, some teachers at the school were horrified by what happened at the parents meeting. And they wanted to make sure the new students felt welcomed. Here's Nedra.

Nedra Martin

I mean, they celebrated that the transfer students were there.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Were you there?

Nedra Martin

I was there.

Nikole Hannah Jones

So you followed the bus?

Nedra Martin

I did, I did, I did.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Can I just say that during desegregation, this is what parents did? They put their kids on the bus to go integrate the schools, and they followed behind because they needed to make sure their kids were OK.

Nedra Martin

Yeah. Just see how she was on the bus. You know?

Nikole Hannah Jones

Just make sure she was OK.

Nedra Martin

Yeah, yes.

Nikole Hannah Jones

You must have just exhaled.

Nedra Martin

Exhaled. I told myself, "OK, it's all good. She is going to be OK."

Nikole Hannah Jones

That day, Mah'Ria was just the new kid in a new school, trying to make her way through her first few classes.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

The first person that I met at Francis Howell was Brittany. I love her. I didn't expect to make a friend that fast, because I remember I think it was after my third or fourth hour, I had went to lunch. I didn't know where to sit or anything like that. So I sat at a table where a couple of girls were, and I just sat there. And then she came over and she's like, "Hi, my name is Brittany." And I was like, "Hi, I'm Mah'Ria." And she just really got to know me.

And it was great. Every day, I would see her in the hall and we smiled very big. It was great, because I never expected to have a long term friend like that.

Nikole Hannah Jones

"Friend like that" meaning a white friend. Mah'Ria had never had a friend who was white before. Mah'Ria's story sounds kind of like an integration fairy tale, but it wasn't that way for everyone coming from Normandy.

Rihanna Curtain is a year below Mah'Ria. She also earns good grades. And she decided to research Francis Howell herself on the internet. She told her mom she wanted to go. She started seventh grade in the Francis Howell district, but in a different middle school than Mah'Ria.

Rihanna Curtain

We got tried. People tried us almost every day. After a week, you was ready to go crazy, because you're not used to nobody calling you out your name. And you don't want to do it, because then what they heard about you is true. So you've got to figure out, "OK, how can I stand up for myself without proving to them that Normandy is ghetto?" And that was the very hard part.

Nikole Hannah Jones

What types of things would people say or do?

Rihanna Curtain

My first week there, this girl, she tried me like-- how can I say this? She ain't know me and I ain't know her. And she was trying to fight me over nothing. Because she ain't like my presence, she wanted to fight and she called me a black B-I-T-C-H and a nigger who wasn't going to know nothing, who was stupid, and ghetto, and trashy. So I'm like, "I'm not going to fight you and then I get kicked out and you look like you were right."

Nikole Hannah Jones

Was that the first time you'd been called that word by a white person?

Rihanna Curtain

Yeah.

Nikole Hannah Jones

And what did that feel like?

Rihanna Curtain

I felt like somebody was stabbing me in my back. It really hurt.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Rihanna thought about leaving and going back to Normandy. Her mom told her she could if she wanted to. She thought about it again and again, but she could not get that girl who called her names out of her head.

Rihanna Curtain

Because I feel like if I was to run away, if I was to come back, she was winning. And I had to prove her wrong. I had to prove to her I'm not stupid, I'm very intelligent. And just because I went to Normandy, that doesn't define who I am neither.

Nikole Hannah Jones

It was hard for Rihanna but she ended up having a good year. So good that one of Rihanna's teachers even asked her to help the girl who called her names with her math, something that Rihanna found ironic, given that the girl had called her stupid. So no, it wasn't always easy, but Rihanna and Mah'Ria both made it through their first year Francis Howell. It was going well, that is until the grownups came up with a new plan.

Ira Glass

Nikole Hannah Jones. Coming up, Adults to the Not Rescue. That's in a minute from Chicago Public Radio when our program continues.

Act Two: The Problem We All Live With PART TWO

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Our program today, The Problem We All Live With. If you're just tuning in, we're telling the story of the Normandy School District that Michael Brown graduated from. In the 2013 to 2014 school year, Mah'Ria, who we heard in the first half of the show, finished eighth grade at the mostly white Francis Howell School District.

Meanwhile, the same year, the mostly black Normandy District that had lost its accreditation, was still operating, though barely. The way the transfer law works, the failing district has to pay to educate its students, even if they leave. So Normandy was paying for 1,000 students to be educated in accredited districts elsewhere, like Francis Howell. It also had to pay for transportation for the students. Altogether, it was $10.4 million that year. Everybody expected that losing a quarter of the students in the Normandy District would be bad. Nobody knew just how bad it was going to turn out. Again, here's Nikole Hannah Jones.

Nikole Hannah Jones

It didn't take long before the transfer law was bankrupting Normandy. By the fall of 2013, the impoverished Normandy District was sending more than a $1 million a month to whiter, wealthier ones. Back at the height of the St. Louis desegregation program in the 1980s, they had a term for this-- black gold.

While wealthier districts were getting an influx of cash, Normandy was careening towards financial insolvency. It shut down a school. The district had to cut staff. That's when the state made a desperation move.

Newscaster

As the day ends, so does the Normandy School District, or at least--

Nikole Hannah Jones

The state was taking over the Normandy District. At first, nobody knew what that meant. Douglas Carr, the Normandy teacher, says they received no explanation.

Douglas Carr

Rumors start flying around, they were going to dissolve the district and that students were going to be sent all over, other places.

Nikole Hannah Jones

If Normandy folded, all of its students, an additional 3,000 of them, would have to be absorbed into other school districts. Bankruptcy, it turns out, will be the ultimate integration plan. So instead, the state took over. And its first big move was to give the district a new name.

Douglas Carr

It was Normandy School District, and now it is Normandy Schools Collaborative.

Nikole Hannah Jones

The Normandy Schools Collaborative. But this was more than just rebranding. According to the state, a shiny new name also came with a shiny new accreditation status.

Douglas Carr

We weren't an unaccredited district. We were non-accredited.

Nikole Hannah Jones

The difference between unaccredited and non-accredited, those three letters, changed everything.

Douglas Carr

We were the only non-accredited district in the world.

Nikole Hannah Jones

So the state says, "We've taken you over. We've given you a new name. And now you have a new accreditation status that has never existed in history of the state."

Douglas Carr

And because we're non-accredited, the transfer law no longer applies. OK? Students who transferred now do not necessarily have the right to stay in that situation. They have to come back.

It's confusing, I know. So let me repeat-- the Normandy School District was unaccredited. But the new Normandy Collaborative District was non-accredited. Now that the district was no longer unaccredited, according to the state, the 1,000 students who had escaped now had to come back.

Nedra Martin

On July 29, I found out, via mail--

Nikole Hannah Jones

Nedra Martin remembers getting the letter when Mah'Ria was at a camp for the Francis Howell volleyball team.

Nedra Martin

Francis Howell is no longer accepting any students from the Normandy because Normandy is now called the Collaborative something.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Normandy Schools Collaborative.

Nedra Martin

That's it. That's it. You know, I'm talking to myself, "Surely, this is a mistake. Not my daughter. That's a mistake."

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

Yeah, I had come from camp, I think it was three days. I got my t-shirt and everything. I still have it to this day-- Francis Howell Volleyball Camp. And she was like, "Mah'Ria, I gotta tell you something." And I could see in her face that it was not good. So she told me, and I'm like, "Oh, my Jesus. What?" "You can't go back to Francis Howell. You've got to go back to Normandy." "Uh, excuse me. Come again? What did you just say?"

Nikole Hannah Jones

So Nedra found herself back in her car on lunch breaks, making calls. She called Francis Howell administrators and teachers and extolled the virtues of her daughter. She told them Mah'Ria was an honor student at Francis Howell and that she stood out on the volleyball team. Nedra found herself pleading for an exception. But Francis Howell was firm. It was not going to be taking any Normandy Collaborative transfers.

Nedra Martin

I literally, mentally, had a vision of a herd of cattle being pushed on a truck, being herded back to where they came from.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Mah'Ria had spent a year making new friends, joining sports teams, settling in. Now she'd be leaving. Think about how this would feel if you were 14, about to enter ninth grade. Mah'Ria shut down. She didn't tell any of her friends at Francis Howell she wasn't coming back, not even Brittany. She just disappeared.

When the state took over, it fired all the teachers over the summer. And then, scrambling, it rehired some of the same ones before the school year started. Morale was incredibly low. This was last August, almost a year ago. Michael Brown was killed August 9, nine days before school started. Michael Brown was buried in the cemetery alongside Normandy High School's football field. He'd just graduated three weeks before.

Mah'Ria started her freshman year at Normandy High School. In the meantime, a group of parents, including Nedra, had filed a lawsuit against the state and were crossing their fingers that a judge would intervene. And eventually, a judge sided with the parents. He wrote in his ruling, "Every day a student attends an unaccredited school, the child could suffer harm that cannot be repaired." He said that Normandy students should be allowed to leave.

But even after that, Francis Howell forced every Normandy student who wanted to return to get his or her own personal injunction from the judge. Again, Francis Howell did not respond to requests to talk to us. For nearly three months, Mah'Ria tried to make it work at Normandy High School. But finally, she gave up and transferred back to Francis Howell. Last month, she completed her freshman year. She's continued to do well.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

Right now, I want this school to be the school that I stay at for my sophomore, junior, and senior year. I don't want to keep flip-flopping between schools, so I'm hopeful that I'll stay. I'm just really settling, enjoying my time at Francis Howell, just in case that ends.

Nikole Hannah Jones

A lot of Normandy kids opted to stay put, even Rihanna, the girl who was called a racial slur in the lunchroom and was determined to stay at Francis Howell. The back and forth just wore her down. She decided to stay. She's paid a cost for staying.

Here is what the last few months at Normandy Middle School have been like. The principal at Rihanna's middle school, not even a year into the job, resigned. And at Rihanna's graduation, the vice president of the Missouri State Board of Education spoke. He apologized to the graduates, he said the state owed students, quote, "A collective apology for failing to provide you with the education experience you should have." In all of my years of reporting, I don't think I've ever heard a state official apologize to students for failing to educate them.

The guy who now has the job of transforming the Normandy schools is Charles Pearson. He's the third superintendent in three years. When we meet in Normandy, Charles Pearson is dapper, in a gray pinstripe suit and bowtie. He has a long track record in education, but until he was asked to lead Normandy he had never spent a day as the head of the school district. Still, he sounds like any other superintendent of a struggling district. He's a cheerleader and upbeat about the potential for a turnaround.

CHARLES PEARSON: We need to really create a new Normandy.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Tell me what does turning around Normandy look like.

CHARLES PEARSON: I think, well, the first indicators of a turnaround is if within three years, at the end of our third year, all of our schools will be accredited again. We're doing the things that improve instruction. We are.

Nikole Hannah Jones

When I hear this, and I've written about these types of schools for a long time--

CHARLES PEARSON: Sure, of course.

Nikole Hannah Jones

What you're saying is, small, incremental progress. But meanwhile, there's kids in those classrooms.

CHARLES PEARSON: Mm-hmm.

Nikole Hannah Jones

There are kids who are going through these schools and not getting the education that they deserve while everyone's trying to fix it. It's not like those kids are removed somewhere and getting a good education while you guys figure it out.

CHARLES PEARSON: Right.

Nikole Hannah Jones

There's kids. There's kids who, for the last three years, have been going through utter chaos. And when they graduate, they're absolutely going to be behind. And I just wonder why is this OK?

CHARLES PEARSON: No one has ever argued it's OK. No, that's not the argument, that it's OK.

Nikole Hannah Jones

But by virtue of what is happening--

CHARLES PEARSON: Yeah, but I'm not saying-- I think it's the reality of where they are, and it's the reality that they're struggling. But if we were OK, we wouldn't be fixing it. It's not OK. There are lives. You asked me a minute ago why would I be doing this? It's 4,000 black kids. It's 4,000.

Why would I say yes? Why would we keep pushing forward when the legislature may make us close? It's 4,000 black kids. So for whatever time we have, they will get a quality education. They will get that. Because we know exactly what to do.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Can I just say, with all due respect, I've had this conversation with superintendents and principals in districts that look just like Normandy and schools that look just like Normandy for more than a decade. And you can look at districts and schools with the same racial makeup in every urban community across the country. And the same thing is said, "We know we need to do." But the schools do not turn around. Typically, an entire district does not turn around.

CHARLES PEARSON: Yes, an entire district has never turned around. It has never happened. But that doesn't relieve us of the charge to attempt to do it. So you're right, it hasn't been done. However, our obligation to attempt to do it, it still remains. The kids are here. So you're right. It hasn't been done. But it's our watch.

Nikole Hannah Jones

So then knowing that, knowing that in these high poverty segregated districts the students aren't doing well, is it possible for a black child in Missouri to get an equal education?

CHARLES PEARSON: Wow, what a great question. The answer right now, I really don't know.

Nikole Hannah Jones

Here's what the evidence shows. A few weeks after I met with Charles Pearson, a reporter from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch named Elisa Crouch spent the day following a Normandy senior to all of his classes. She chose Cameron Hensley, a driven honor student. She met him at Normandy High School in time to head to his first period.

Elisa Crouch

We went into AP English, and it's held in a science lab. The classroom across the hall, where it should be held, smells like mildew and the ventilation system doesn't work. I looked around. Stools were up on tables. There was one other student, his friend, Arianna, and Mr. Drummer, the AP English teacher who is not certified to teach AP English, who at that moment was not in the classroom and who would just come and go.

Nikole Hannah Jones

She says at some point Mr. Drummer gave the two students a worksheet. This was advanced placement. That's the highest English class the school offered. But Elisa said the worksheet looked to be at the middle school level. Cameron and other students finished in five minutes. They had 40 minutes left.

Elisa Crouch

Second period was jazz band. We went down to the jazz room, the jazz band room, and the instructor was not there. There was no substitute teacher. So Cameron said he normally goes to the counselor's office because this was not unusual. And we spent that whole entire hour talking about what his ambitions are, his history in the Normandy school system, and how he regretted not leaving.

Third period physics class teacher, who is a permanent sub, hasn't taught since January, hasn't planned a lesson since then. Fourth period was precalculus taught by a retired teacher who does care and was teaching something. I went to lunch with Cameron. Then was choir, and then he had two periods of band. And so that was pretty much the rest of the day.

Nikole Hannah Jones

So four periods of music, three academic classes, one where a teacher actually taught. It's hard to imagine a bar lower than that. And Cameron's an honor student. For his part, Pearson, the superintendent, said he was shocked to read in the paper what was happening, or more accurately, what was not happening at the high school.

While Normandy is falling apart, over at Francis Howell, none of the things that parents were worried about came true. No one got stabbed. Test scores did not drop-- at all. And at least so far, the influx of black students hasn't caused white parents to flee. Mah'Ria's thriving. Where the transfer law forced integration, it's working.

The educational devastation in Normandy has finally gotten the attention of the state's most powerful people, including state legislators and the governor. The law says they can't keep the Normandy kids in schools that aren't accredited. So they're proposing charter schools and virtual school programs that students would attend. They're sending in teacher coaches from wealthier districts. The idea is, try anything they can to keep Normandy students inside the district. This is how far they will go to avoid that one thing, that one thing that already seems to be working-- integration.

Ira Glass

Nikole Hannah Jones, she's a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine. She also did a great story about the Normandy schools for Pro Publica. You can read that at their website, propublica.org. And she's written this amazing article-- I cannot recommend this highly enough-- about choosing a school for her own kid in New York City's segregated school system. That's at The New York Times website.

[MUSIC - SYL JOHNSON, "IS IT BECAUSE I'M BLACK?"]

Credits

Ira Glass

Our program was produced today by Chana Joffe-Walt and Jonathan Menjivar with Zoe Chase, Sean Cole, Stephanie Foo, Miki Meek, Robyn Semien, Alissa Shipp, and Nancy Updike, editing help from Joel Lovell. Julie Snyder was the consulting editor for this episode.

Other editing help for this episode from Neil Drumming. Production help from Emmanuel Dzotsi. Our technical director is Matt Tierney. Our staff includes Elise Bergerson, Emily Condon, Kimberly Henderson, and Seth Lind. Research help today from Michelle Harris. Music help from Damian Graf from Rob Geddis.

Our website, thisamericanlife.org. This American Life Life is delivered to public radio stations by PRX, the Public Radio Exchange. Thanks as always to our program's co-founder, Mr. Torey Malatia. You know, he finally explained to me why he showed up at work wearing hiking boots and a suit covered in dirt.

Mah'Ria Pruitt-Martin

I had come from camp, got my t-shirt and everything. I still have it to this day.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass, back next week with more stories of This American Life.