427: Original Recipe

Note: This American Life is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Act One: Message In a Bottle

Ira Glass

Hey there, everybody. So I'm not going to beat around the bush. For this week's radio program, we think we may have found the original recipe for Coca-Cola. And I am not kidding. I am not kidding. One of the most famously guarded trade secrets on the planet, I have it right here, and I'm going to read it to you. I'm going to read it to the world. And I'm going to make my case for why I think it's real, despite whatever Coca-Cola might say. And that is just one of the two stories on today's program.

From WBEZ Chicago, it is This American Life, distributed by Public Radio International. I'm Ira Glass.

Act Two: Ask Not What Your Handwriting Authenticator Can Do for You; Ask What You Can Do for Your Handwriting Authenticator

Ira Glass

Probably the best story about how protective Coca-Cola is of its secret formula comes from this book that was written by Charles Howard Candler. His Dad, Asa, did not invent Coca-Cola, but founded the Coca-Cola company back in 1892.

And Charles, the son, wrote this. "One of the proudest moments of my life came when my father initiated me into the mysteries of the secret flavoring formula, inducting me into the holy of holies." Charles then says, "Incredibly there was no written formula and the labels had been removed from all the containers of the ingredients." So they were, quote, "identified only by sight, smell, and remembering where each was put on the shelf. And I thereupon experienced the thrill of making up, with his guidance, a batch of merchandise 7x." Merchandise 7x. Merchandise 7x is the cartoonishly super secret, cloak and dagger name they give the flavoring mixture in Coca-Cola.

Charles' dad, Asa, was so paranoid about anybody else getting hold of the secret formula for 7x that, even though he was president of Coca-Cola-- he's president of the company-- he would go through the company mail himself and remove the invoices for any ingredients that had been purchased, so that nobody in the accounting department could read what ingredients had been bought for the product. I learned all this from a history of Coca-Cola, a book written by investigative journalist and historian Mark Pendergrast.

Mark Pendergrast

The company has always said, and as far as I know it's true, that only two people at any given time know how to actually mix the 7x flavoring ingredient. And that these people never travel on the same airplane in case it crashes. It's this carefully passed on secret ritual. And that the formula is kept in a bank vault at Sun Trust, which used to be the Georgia Trust Company.

Ira Glass

Of course this makes no sense at all. Why can't the two guys fly on a plane if the formula is sitting inside a bank vault? Coke's official line on this these days is that they simply do not talk about how many people know the recipe. Though the reason that most of us think that of it as one of the biggest trade secrets in the world is probably because that's the story Coca-Cola likes to tell.

Announcer

Coke's secret formula. Only two guys in the world know it. If something happened to one, the formula would be lost forever. And then, cookouts would be catastrophic.

Ira Glass

In this particular Coke commercial, I guess the premise is that each of the two guys only knows half the formula. It's just one of several commercials that have come out recently that poke fun at the myth of the super secret formula, while at the same time bolstering and selling that myth.

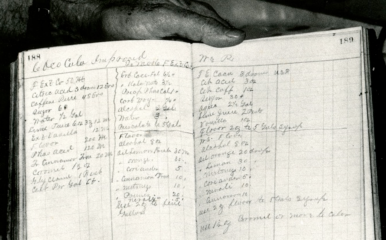

Coke even has this thrill ride at its museum in Atlanta, The World of Coca-Cola, where you follow two characters who are trying to unlock the secret formula for Coca-Cola. So with all this money, all this energy, all these millions of dollars spent over the years to convince us of just how impossibly, importantly, iconically secret the formula to Coca-Cola is, it was, a surprise when we stumbled across an article in Coke's hometown paper, the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, February 18, 1979. Not on the front page, but buried. Buried back on page 2B. One of their columnists, Charles Saulter, without any fanfare at all, published what looks like the original recipe for Coca-Cola.

He found it in a pharmacist's old book of recipes. All the recipes, including the one for Coca-Cola, are written by hand. Most of them are for various ointments and remedies.

And if that seems like a strange and random place to find this kind of thing, well, Coca-Cola was invented by a pharmacist, and it was originally sold at pharmacy soda fountains. The article says that the book passed from one pharmacist to another until it fell into the hands of one Everett Beal, who owned a drug store in Griffin, Georgia, 40 miles from Atlanta. He is mainly identified in the story as a fishing buddy of the columnist.

Judy

Hello?

Ira Glass

Judy?

Judy

Yes, you're late.

Ira Glass

I know I am.

Judy

Did you have a nice flight back home?

Ira Glass

Everett Beal passed away July 2010. I called his widow Judy at her home in Georgia so many times asking for an interview that at one point she said to me, "This is how you people won the war, isn't it?" "You people" meaning northerners.

Judy

And you wanted to know how Everett got this book?

Ira Glass

Yes.

Judy

Well RR Evans was a good friend of Pemberton's.

Ira Glass

OK, let's just pause the tape right there to explain who these guys are. The Pemberton that she's talking about is John Pemberton, the guy who invented Coca-Cola in Atlanta back in 1886. Like I said, he was a pharmacist. But he was also a maker of patent medicines. He made something called Globe Flower Cough Syrup. He made a blood purifier called Extract of [? Stalengia. ?]

RR Evans-- that's the second person that she mentioned-- Judy says, was another pharmacist in Atlanta at the time.

Judy

And they were best friends and blah, blah, blah.

Ira Glass

This book of recipes, Judy says, originally belonged to Evans. She says his name is all over the book. Apparently after his friend Pemberton invented Coke, Evans copied down the formula in this book, calling it Cocoa-Cola

Judy

That's right.

Ira Glass

And after Evans died, the book started its travels.

Judy

Evans gave it to RM Mitchell from Griffin, Georgia. And then Mitchell's widow was a friend of my husband's and told him, after he passed way, to come over and get any books he wanted to out of the library. So Everett picked out the book.

Ira Glass

What's it look like?

Judy

Oh gosh, it's 133 years old. It's just leather bound. And I wear gloves-- the last time I looked at it, I like to wear gloves.

Ira Glass

Everett was so intrigued by the Coke recipe that he spent the last year of his life while he struggled with cancer researching and writing his own book, a history of the inventor of Coca-Cola, that's still unpublished.

Interestingly, just like the characters in Lord of the Rings when they get a hold of the ring, once Everett had the secret formula, like the people at Coca-Cola, he started to get protective. The recipe book now sits in a bank vault. Take his reaction when his fishing buddy, Charles, did the 1979 newspaper story about the recipe book. the newspaper published a photo that was big enough that you can read all the ingredients and the amounts, the entire recipe.

Judy

See, Charles did that, and Everett was unhappy about that.

Ira Glass

Oh, he was?

Judy

But I won't go into that.

Ira Glass

Oh, really?

Judy

Yeah.

Ira Glass

And was he happy that there was an article?

Judy

Yeah, but not the formula page.

Mark Pendergrast

Oh, here it is. Yeah, so I'm looking at it here.

Ira Glass

We sent a copy of that photo where you can see the recipe for Coca-Cola to that historian of Coca-Cola, the guy who wrote that book, Mark Pendergrast.

Ira Glass

And my question for you is, could this be real?

Mark Pendergrast

Yeah. I think that it certainly is a version of the formula. And it's very, very similar to the formula that I found that I talked about and printed in the back of my book.

Ira Glass

This was an amazing discovery. In Mark's book he tells the story of looking through Coca-Cola's archives and being shown the yellowing pages of an old notebook that belonged to the inventor of Coca-Cola, John Pemberton. The Coke people told him that it was from way before Pemberton moved to Atlanta, way before he invented Coke.

Mark Pendergrast

But in fact, it was quite clear that it was a formula book from at least after he'd invented Coca-Cola, because it mentioned Coca-Cola.

Ira Glass

Oh, so do you think they just didn't know?

Mark Pendergrast

Apparently not. So in this formula book there was a piece of paper that had a big X on the top of it. And as I looked at it, I thought, I saw this flavoring ingredient. It had neroli. It had coriander. I though, my God. This is a Coca-Cola formula. I couldn't believe it.

Ira Glass

And did the company confirm that that's what this was?

Mark Pendergrast

Of course not. The company denies that that's what it was.

Ira Glass

New York Times May 2, 1993, the year Mark's book was published, Coca-Cola calls the recipe in his book, quote, "The latest in a long line of previous unsuccessful attempts to reveal a 107 year old mystery."

But here's where things get interesting. When you compare these two recipes, the one that Mark found in John Pemberton's own notebook, stored deep inside Coca-Cola's very own archives, and the one from the 1979 newspaper clipping found 40 miles away in Griffin, Georgia--

Mark Pendergrast

Oil of lemon.

Ira Glass

--not only do they match up ingredient for ingredient, identical--

Mark Pendergrast

Oil of coriander.

Ira Glass

--the recipe in the newspaper fills in things that the one in the Coke archive leaves blank. The recipe from Coke's archive just lists numbers next to each ingredient. But the newspaper says what the numbers stand for: ounces and drops and drams. The recipe that was found in Coke's archive is just labeled X. The newspaper one says clearly, this recipe is Cocoa-Cola.

I got into this wondering if it might be possible that this super secret recipe had been hiding in plain sight in an old newspaper clipping for decades. But once I learned that it actually matched this recipe in Coke's own archives, written by the creator of Coke, it was hard not to get very excited. These last two weeks I've been carrying around a printout of the recipe everywhere I go, this one that I have right here with me in the studio today. And I've been telling everybody I see, I think I may have found the secret formula for Coke. And then I just watch them freak out.

So now, right here on the radio, I will read you the formula. You have heard the facts. You can draw your own conclusions as to what this is.

Oh, wait, but first--

Ira Glass

Is it legal for us to even talk about this on the radio? Is Coke going to sue us both?

Mark Pendergrast

No, I don't think they will. Because if they sued anything pertaining to the formula, then they would have to then produce the formula in order to say that what you were doing was an infringement on their formula. And they will never do that.

Ira Glass

Great. Here we go. The 7x formula is just one element in these two recipes. It's made from 20 drops of orange oil, 30 of lemon oil, 10 of nutmeg oil, 5 of coriander oil, 10 of neroli oil-- neroli's a kind of orangey flavor-- 10 of cinnamon oil, and 8 ounces of alcohol. You mix that together, and then you take a little bit of that flavoring. One recipe says two ounces, the other says two and a half. You put that into another container where you're going to mix the syrup for the soda.

The other ingredients, 3 ounces citric acid, 1 ounce caffeine, 2 and a 1/2 gallons of water. The recipe calls that aqua. 2 pints of lime juice, an ounce of vanilla, 1 and 1/2 ounces of caramel coloring. And then we arrive at the two most controversial ingredients in Coca-Cola. 30 pounds of sugar-- pounds-- and at the very top of the page, first ingredient, FE coca, which stands for fluid extract of coca. That'll be the flavor of the coca leaf, which includes a small amount of cocaine.

In fact, Mark says that cocaine figures in a big way in the creation of Coca-Cola. Before he invented Coke, John Pemberton had a hit with another drink called French Wine Coca. It's ingredients: wine, cocaine, and caffeine. Hard to see why people went for that one, right?

Then, in 1885, Atlanta voted for prohibition, and Pemberton realized that he was going to have to get rid of the wine in his bestselling drink. So he kept the two other ingredients, the cocaine and the caffeine. People loved those. But when you mix cocaine and caffeine together, they're bitter. So he pours in a ton of sugar to cut the bitterness and voila, Coca-Cola. Pemberton called it his temperance drink.

Mark Pendergrast

I mean, this is an interesting thing. They still do use coca leaf for Coke, but they decocainize it in Maywood, New Jersey at the Stepan Chemical Company, which was--

Ira Glass

Wait. So there's a plant in New Jersey, and basically they import tons and tons of coca leaves. They remove the cocaine from the coca leaf?

Mark Pendergrast

Correct. And it's been decocainized there since 1903.

Ira Glass

1903 being the year that Coca-Cola rids itself of cocaine. So there's all this circumstantial evidence pointing to this recipe being the original recipe for Coca-Cola. Or at any rate, one of the original recipes. But the only way to tell for sure would be to make a batch. Taste it. The historian had never done that, the columnist back in 1979 never did it. That would be the final test. So we set out to do it.

Ben Calhoun

This is it. This is it at the top, the first one up there.

Ira Glass

First obstacle in our path, kind of a huge one-- coca leaves are a Schedule II controlled substance. Totally illegal in the United States. When we asked the company that brings them in under special federal supervision and decocainizes them for Coca-Cola, this company Stepan, and asked them to sell us some, they stopped returning our calls. No coca leaves, no way to make the secret recipe.

But then, my fellow This American Life producer Ben Calhoun turned to an obscure back alley resource called the internet.

Ira Glass

Wow, look at this. I just typed coca tea into the search. 5, 6, 7-- there's like a dozen things. More than a dozen, 15, 20 things come up which are coca tea just in amazon.com.

Ben Calhoun

So the way that Coke does it with taking the cocaine out, this company says that they do the same thing.

Ira Glass

So the hardest part was done, except for making the soda. For that we turned to professionals.

Ira Glass

When we first sent you guys this recipe and you took a look at it, can I just ask you, what did you think when you saw the ingredients?

Eric Chastain

It was pretty dizzying for me.

Mike Spear

Yeah, I mean it took a little while to sort of translate the handwriting and figure out what it was.

Ira Glass

Meet Eric Chastain and Mike Spear, respectively the VP of operations and the marketing director at Jones Soda in Seattle. Jones makes it living on flavors like cream soda and green apple soda. But they're also known for being willing to try anything. They have made turkey and gravy soda, they've made Brussels sprout soda. We sent them our recipe, and by the time that Ben and I got to their office, Mike and Eric had already made up a couple bottles of our recipe and were ready for a taste test. Our stuff versus real Coca-Cola.

Eric Chastain

This is the first bottle of Coke we've ever had in this office.

Mike Spear

Just get it out as soon as we can.

Eric Chastain

Yeah, just get rid of it.

Ira Glass

We were worried that asking you guys to go out and make Coca-Cola was like asking you to like go into the Death Star and blow up some planets or something.

Eric Chastain

There was a little debate over that.

Mike Spear

There was a debate. Yeah, for sure.

[POURING]

Ira Glass

First, samples from our soda, the one from the 1979 newspaper, are poured into little cups. We're instructed to sniff first, then take a small sip, roll it around in our mouths. We really do not know what to expect.

Ira Glass

I have this feeling like I'm going to drop acid right now.

Mike Spear

It's kind of tasty.

Eric Chastain

It is kind of tasty. It's not bad. It's definitely got a medicinal note to it.

Mike Spear

Yeah, it does.

Ira Glass

I find it to be really mediciney. And if you didn't tell me that this was the Coca-Cola recipe, I wouldn't have known. It tastes fruity.

Eric Chastain

Yeah.

Mike Spear

It does taste a little fruity.

Ira Glass

Ben says the flavor is like Froot Loops. To me, it's more like orange-flavored baby aspirin. Which means, we failed, right? We made the recipe. You would never mistake it for Coca-Cola. But then it occurred to us, maybe the original version of Coca-Cola did not taste like Coke today.

Charles Candler, that guy who was taken into the holy of holies to learn the secret recipe from his dad, wrote this, "The Pemberton product--" that is the original product-- "did not have an altogether agreeable taste. It was unstable. It contained too many things. Too much of some ingredients and too little of others. The bouquet of several of the volatile essential oils previously used was adversely affected by some ingredients."

That could be the lime and baby aspirin flavored mess that we had just tried. But there was another possibility. The soda guys thought that technology has gotten so much better at extracting flavors like orange oil and lemon oil from fruits in the last 125 years, it's possible that all our ingredients are much, much stronger than Pemberton worked with back in 1886.

David Ames

David Ames.

Eric Chastain

David, it's Eric and the rest of the gang at Jones.

Ira Glass

So Eric and Mike called the flavor company that they're working on with all this-- it's a company that specializes in beverage flavors called Sovereign down in Orange County, California-- and asked if they could do a version that tones down the citrus and other flavors.

Eric Chastain

Maybe reduce, I don't know, maybe 5, 10%.

David Ames

OK, got it.

[BOTTLES JANGLING]

Woman

Chemicals are all over here.

Ira Glass

A few hours later we have flown south to Los Angeles. We are in Sovereign's lab, a room that smells like you're inside a bag of jelly beans. And we do a second taste test.

Mike Spear

All right, so we've got the revised cola on the left and then Coca-Cola on the right.

Ira Glass

In the lab with us and Mike from Jones Soda were David Ames, who runs the flavor company, and his staff. Going with the idea that our essential oils were much stronger than Pemberton's, they ended up cutting the amount of flavor in half. And then they tried it and they thought, oh, let's cut it in half again.

David Ames

It's interesting. It's definitely more mellow.

Mike Spear

But also, the flavor profile is almost at the same intensity as the Coke flavor profile.

David Ames

I feel like you guy just knocked off Fort Knox.

Ira Glass

We look at each other like, what had we done?

Ira Glass

How close do you think you are to the taste of actual Coca-Cola now?

Man

I would say probably, what, on a the scale of 10? We're probably around 9, I would say. 8 and 1/2, 9.

Ira Glass

Later I talked to Steve Warth, the guy who did the heavy lifting in converting that old formula into modern lab measurements. He's the one in charge of developing Sovereign's flavors. He says the ingredients in this old recipe were no surprise to him. Most of them are the same ingredients you use to make any cola.

Steve Warth

Orange oil, lemon oil, nutmeg, and cinnamon would be the main ones. I noticed that the neroli and the coriander seemed higher than what I've seen elsewhere.

Ira Glass

Steve said that if we ever decided to match Coca-Cola the way it tastes today, lots of things about the formula are widely known. We'd have to replace the citric acid in the old formula with phosphoric acid. That's what modern sodas use. We would replace the lime juice with lime oil. We'd swap this sugar for high fructose corn syrup.

Steve Warth

I know in some of the other flavor companies that I've worked at, we've worked on trying to get as close. We've had customers that come in and say, I want an exact match for Coke. And they're usually pretty close.

Ira Glass

So basically, this idea of Coke, it's the super secret thing that nobody could crack, from your perspective, that's just some very cheerful showmanship on their part.

Steve Warth

Well, actually, no. It isn't. If you wanted to go side by side and match it exactly, that's very difficult. And that's not only difficult for Coca-Cola, it's difficult for everything.

Ira Glass

That's because even if you know that there's say, cinnamon, in a drink, you don't know where it came from-- Sri Lanka, Indonesia. And that can make all the difference in the flavor. I asked the flavor guys at Sovereign if they could pick out the real Coca-Cola from our formula in a blind taste test.

David Ames

I'd be able to tell.

Man

Yeah, there's probably a good chance that we will. Yes.

Ira Glass

So we marked the little plastic cups which had real Coca-Cola with a Sharpie, just a little dot on the bottom of the cup. The cups with our formula had no dot. Everyone tasted. David, the guy who runs the company, was sure that he was drinking our formula. And then he flipped over the cup and saw--

David Ames

Sharpie. I got a Sharpie.

Ira Glass

Meaning he thought our formula was Coca-Cola.

David Ames

I got a Sharpie.

Ira Glass

Do you think ordinary consumers would be able to pick out which one of these is real Coca-Cola?

Man

I highly doubt it. I seriously doubt that. I think if we would do a blind test right now with a regular consumer, I think we will be able to fool them.

Announcer

Attention all [INAUDIBLE] shoppers. Take a moment to look down at your shopping carts. You may have the wrong cart. If you have the wrong cart, please return it to the [INAUDIBLE] department. Thank you.

Ira Glass

Ben and I put on lab coats and we set up a table in aisle 2B of a supermarket one afternoon with bottles of our soda-- that is, the formula from the 1979 newspaper article-- and Coca-Cola. Taste test time.

One of the first people who came up to us was actually a woman who had worked supermarket tastings herself.

Woman

Use your smiles. People love to see a smile. And when you get a smile back, that's when you're like, hey, you want to [SNAP] try a sample? That's how you know.

Ira Glass

Do I have to make the [SNAP] sound?

Woman 2

No, you don't have to. That's what I do sometimes.

Ira Glass

So Ben and I smiled. With each person we would give them our formula first.

Taster 1

I taste berries.

Ira Glass

And then we gave a real Coke second.

Taster 1

Tastes like RC Cola.

Ben Calhoun

Tastes like RC Cola.

Taster 1

Tastes like a really cheap cola.

Ira Glass

And before we told people what they were, we asked which they liked better.

Taster 2

I liked the first one better.

Taster 3

Probably the second one.

Ben Calhoun

Second one?

Taster 4

Yeah, the second one I prefer.

Ira Glass

60% of the people preferred our formula over Coca-Cola.

Taster 5

The first one.

Ira Glass

Though, to be fair to Coca-Cola, people who said they drank a lot of soft drinks, they always preferred the Coke.

Taster 6

It's better than the first one.

Ira Glass

And when we asked people to guess which of the two drinks was Coca-Cola, to our surprise actually, of the 30 people that we polled, 28 could tell which was Coca-Cola. Our formula was that different. People saw a family resemblance though.

Taster 7

I was thinking it taste more like the old vanilla Coke.

Taster 8

It had an aftertaste that made me stop and think for a minute. But I tell it was somewhere in there or was manufactured by Coke.

Taster 9

It tastes like weird soda trying to be Coke.

Ira Glass

There was just one more person that I wanted to taste the soda that we made and look at the recipe. And that was the Coca-Cola's corporation resident expert on the history of the product and its early formulas.

Phil Mooney

My Name is Phil Mooney. I'm the archivist for the Coca-Cola company based in Atlanta, Georgia. My quick reaction is that it's sweeter and flatter than Coca-Cola. It doesn't have what we call the bite and the burn that Coca-Cola has.

Ira Glass

Does this seem like it could be an ancestor or a relative of Coca-Cola?

Phil Mooney

You know, quite frankly I don't think so.

Ira Glass

I told Phil everything that we knew about the recipe-- the newspaper article it came from, how it matched a recipe deep in his own archives. He was not impressed. Very, very not impressed.

Phil Mooney

And really, this is not unusual. I can't tell you how many people have come forward over the years and claimed to have the formula for Coca-Cola. I probably have three or four dozen examples of that. And they'll say, well, I knew this old pharmacist-- almost the same story that you told me. And he got this recipe from a friend, usually it's a friend of Asa Candler or John Pemberton.

Ira Glass

And do most of them have these same ingredients? They have lime, and they have neroli and cinnamon and nutmeg?

Phil Mooney

Almost all of them are very, very similar, if not identical.

Ira Glass

We went around and around on this. To me, the fact that the recipe showed up over and over gave it credibility. Coke's inventor John Pemberton was known to have sold the recipe to several different people back in the early days. And the fact that it had appeared in his own notebook in Coke's archive seemed like the clincher.

But Phil said that no, no, that notebook, if we were to look at it more closely, was full of all kinds of failed attempts at soda recipes and variations on recipes. So it was hard for him to believe that the real formula for Coke was stuck in there among that stuff.

Phil Mooney

Could it be a precursor? Yeah. Absolutely. Is this one that went to market? I don't think so.

Ira Glass

But we don't know?

Phil Mooney

We're pretty sure. We're pretty sure that the final recipe was not the one represented in that book.

Ira Glass

I asked him if anybody at Coca-Cola who had access to the original recipe, which he says they still have, actually checked to see if it matched the one in that notebook. And he politely side-stepped that question and we moved on.

Ira Glass

And there's all this fuss about the secret formula, but it seems like the basic ingredients of Coca-Cola are actually on the public record.

Phil Mooney

Absolutely.

Ira Glass

So we put it to him. Was the secret formula really a secret? He said that even if somebody cracked the entire manufacturing process, which he said they'd have to do, and produce something very, very close, Coke has this whole of this thing nobody can touch.

Phil Mooney

There's a psychological element to this product. We've got a 125 years worth of marketing and advertising. And people's memories.

Ira Glass

Well in the supermarket, when we were in the supermarket, one of the young women who tasted the product, she tasted an unmarked little cup of Coca-Cola and she said, "That tastes like my childhood."

Phil Mooney

There you go.

Ira Glass

That's what 125 years of omnipresent worldwide distribution and promotion buys you. I told Phil that we were going to put up the old recipe that we found on our website and asked him if it would be OK with Coke if listeners would try to make batches themselves-- all the ingredients and oils that you need are online. They're cheap too. And he laughed and said, "Yeah. Yeah, let them try. They'll come running back to Coke."

Coming up, how much does one of President Obama's old spark plugs sell for, and the search for other historical originals. In a minute, from Chicago Public Radio and Public Radio International when our program continues.

Credits

Ira Glass

It's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass. Today's show, "Original Recipe." Stories of people going to great lengths to find the authentic original item. We have arrived at act two of our show. Act two, "Ask not what your handwriting analyst can do for you; ask what you can do for your handwriting analyst."

When you find an old, authentic original it can, of course, mean lots and lots of money. Jake Halpern tells what happened when somebody stumbled onto a trove of astounding papers, which lots of people thought was worth millions.

Jake Halpern

John Reznikoff buys and sells relics and documents. He's got a sprawling office in Westport, Connecticut that's floor to ceiling history. Old documents hanging everywhere signed by Thomas Jefferson or James Madison or John Hancock. He's got Abraham Lincoln's spectacles in a file cabinet. And in the middle of the room, as if some movers just dumped it there, something that looks like an old school desk.

John Reznikoff

That's Abraham Lincoln's desk. And why is it sitting here? Good question. I need to get it restored.

Jake Halpern

By the way, $325,000, if you're interested. In a back room there's Annie Oakley's gun leaning up against the shelf where Earnest Hemingway's typewriter sits, alongside Franklin Roosevelt's chess set. It's like what you'd see if the Smithsonian had a going out of business sale. The strangest thing that he bought and sold recently was President Obama's old Jeep. It helped that Obama had mentioned the car in a speech at Chrysler.

John Reznikoff

And I put a little clip of that on a YouTube video. And I'll do my best Obama impersonation. "My first car was a Jeep Grand Cherokee. I loved that car."

Jake Halpern

It sold for a lot, though John wouldn't say how much. When the guy who bought it had it repaired, John asked if he could keep the spare parts. He stores them in a closet in his office.

John Reznikoff

I'm not kidding, right. So I guess these are struts. Those are Obama's struts. And [RUMMAGING] in the bottom-- here, I'll grab a spark plug. There. There's a spark plug from Obama's car. I actually just sold one of these for $500 because it was Obama's.

Jake Halpern

Sucker, right? $500 for a spark plug? But five minutes in John's office and you realize, people will buy anything connected to historical figures, assuming it's real.

This business, especially the rare document business, can be risky. There are so many fakes out there. So John is a fanatic about authenticity. He's studied fakes to see how they're made. He owns a huge collection of forgeries he bought from another collector and he uses it as a reference. He can sometimes even identify a particular forger. And part of his office looks like a lab on CSI. He's got a special high-powered magnifier called a proscope, and a video spectral comparator, a $30,000 machine used to analyze ink.

John's called as an expert witness on handwriting in all kinds of court cases. He's a go-to guy in his field for spotting fake autographs.

John Reznikoff

At the risk of sounding egotistical, everybody in the business who wants an opinion on pretty much any presidential person, the first person they come to is me. That's a big change in the 13 years.

Jake Halpern

13 years ago. That's when John's career all but collapsed in a scandal so deep and far-reaching that people are still arguing about what exactly happened. Even John himself isn't entirely sure. He made mistakes he didn't know he could make. Mistakes he didn't even suspect. And for years, he didn't talk about it, until now.

It all started in 1992, when John got a call from a guy named Lawrence X. Cusack III.

John Reznikoff

Very nice, very friendly guy, and he had some beautiful stamps that he was selling that were his father's, his father's collection. And I remember it included some very nice illustrated envelopes from the 19th century. And I bought them in several batches and became very friendly with him. He seemed to be very educated, extremely well polished, very well dressed.

Jake Halpern

The two of them hit it off. They started to hang out on the weekends. John was engaged at the time and Cusack-- everyone called him Lex-- had a pretty young wife. They'd all have dinner at an Italian place. To John, Lex was a kind of worldly older brother. They started confiding in each other.

John Reznikoff

In the beginning, he unraveled his military career, which I thought was the coolest thing I'd ever heard.

Jake Halpern

John had a particular reverence for soldiers. His own dad had served in the Pacific in World War II, and John still talks about the time when he was eight and his father took out his army uniform covered in medals and ribbons, laid it out on the family's ping pong table. Ever since, John had been sort of obsessed with the military. He'd never joined himself, but he was eager to listen to someone like Lex, who told him he'd been in the Navy flying F-16's during Vietnam.

Lex was quiet about it. John had to pry the details out of him. That he'd been downed in Cambodia and survived by hiding in a swamp, breathing through a reed. What really struck John, what blew him away, was when they visited the naval academy in Annapolis. Lex's sister-in-law had been admitted, so they went down for plebe weekend.

John Reznikoff

You know, a very proud group of friends and family. And when Lex came out he was in a completely white uniform, lieutenant commander's uniform because he was a lieutenant commander, wearing the hat, wearing the Navy cross, wearing all the medals on his chest. And there's 3,000 people there and they're all saluting him. And he's giving back-- if you can imagine my hand going to my head-- a perfect salute. And I'm like, wow. I'm with a war hero here right now, and this is my buddy.

Jake Halpern

A few months after they met, Lex got to talking about his father, also named Lawrence Cusack, who died in 1985. Cusack Senior had been a distinguished lawyer. He'd worked for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York for many years, and he was personal counsel to John Cardinal O'Connor, the archbishop. As Lex explained it, he had some pretty high-powered clients.

John Reznikoff

At one point, Lex revealed to me that his dad had worked for the Kennedys. And any time I meet somebody who has any connection with anybody famous, I'm like, where are the papers? You know, the papers are valuable. Anything he signed would be valuable. And a conversation ensued on that. And he said he'd look.

Jake Halpern

A month or so later, Lex mentioned something else interesting.

John Reznikoff

Well then, Marilyn Monroe gets introduced into the equation. My father also worked for Marilyn Monroe. And--

Jake Halpern

Wait, can you just describe how that all goes down?

John Reznikoff

Well, Marilyn Monroe had a New York residence, too, and he said he did some legal work for her. And indicated that there was a relationship that his father helped to hush.

Jake Halpern

When he tells you this, what's your reaction? That's pretty crazy news, right?

John Reznikoff

Yeah. Naturally-- and I think anybody would have this reaction-- you know, the dollar signs are coming in my eyes. I'm thinking, oh my God. This is a career maker for me. This is the treasure that I've been searching for my whole life.

Jake Halpern

And now are you starting to kind of tell him, like, can I see these papers?

John Reznikoff

I'm pushing him. I'm saying, go. Go look for them. Where are they? You know, go get them. Go through the files. You don't know what you might be sitting on. You might be sitting on fortunes. Maybe it's hundreds of thousands, maybe it's millions.

Jake Halpern

JFK and Marilyn Monroe-- this was arguably the most storied love affair and cover up of the 20th century. We've all heard the rumors about it for 50 years. But it's just that-- rumors. No one ever had any hard and fast proof, until-- maybe-- now. He forced himself to be patient as Lex searched through his father's extensive and mysterious files. John can't quite remember how long he waited. Maybe weeks or even months, until one day Lex finally shows up at his office with a discovery in hand.

John Reznikoff

He brought in a briefcase into the office, and I remember there was a document that I believe was on a sheet of stationery that was written in Kennedy's hand. And it sure looked like Kennedy to me. And it basically was written to Marilyn Monroe, and indicated some kind of payoff. He agreed to pay something, or give her something, or set up a trust, I think it was.

Jake Halpern

In other words, jackpot.

John Reznikoff

"Agreement made this third day of March, 1960, between John F. Kennedy, residing at the Carlyle Hotel, New York, New York, and Marilyn Monroe, residing at 444 East 57th Street, New York, New York. Witnesseth, whereas a result of a relationship between Marilyn Monroe, herein referred to as MM, and John F. Kennedy, herein referred to as JFK. MM believes she has suffered irreparable harm to her well being and to her professional life and career. And that such has been the cause of personal hardship and suffering, which is not possible to measure. MM shall never discuss nor reveal to any persons the specifics of the said relationship between her and JFK."

Jake Halpern

And there were other documents like this one. Lex kept finding them. Letters on Kennedy's US Senate stationary, on White House stationary. There were index cards and personal notes. The documents prove JFK's relationship not just with Marilyn Monroe, but with other, sketchier characters as well.

John Reznikoff

This is a memorandum. And shall I read some of it?

Jake Halpern

Yeah.

John Reznikoff

"Monroe will refrain from discussing her knowledge of any meetings or discussions of any kind which may have taken place at which were present JFK and Giancana."

Jake Halpern

Who's Giancana?

John Reznikoff

Sam Giancana.

Jake Halpern

That the mob boss?

John Reznikoff

Yes.

Jake Halpern

I mean, are you nervous holding these things in your hand for the first time when you're doing it?

John Reznikoff

I'm nervous on a number of levels. I was scared. I'm thinking that this is really dangerous stuff. How do I handle this? Is this too big for me? How am I going to do this? How am I going to do it right? And also, what's going through my head is, oh my God. Here it is. The Holy Grail. Oh my God, this is worth a lot of money.

Jake Halpern

In all, Lex unearthed more than 300 documents, a whole archive. And John, of course, considered that maybe, like the Holy Grail, it was too good to be true. So he set about authenticating the papers. He went to at least half a dozen experts in the field, not just handwriting experts, but people who specialize in Kennedy documents. But John didn't want the contents of the papers to get out. He wanted to protect their value, so he sent the experts only a few documents each. Or sometimes portions of documents he'd Xeroxed, excluding the juicy parts.

John Reznikoff

And each one, one by one, authenticated them and said they were real.

Jake Halpern

One of these experts was John's mentor and a giant in the field, Charles Hamilton.

John Reznikoff

And right away he looked at it. If you look at that book right there where it says The Robot. OK, that's all about John Kennedy's handwriting. So here's the guy that wrote the book. And he looked at it, maybe spent 10 minutes with it. This is authentic. And wrote a letter on it. And that gave me tremendous confidence. It's an important moment for me. It's everyday business for him, because he doesn't know, really, what this signifies.

Jake Halpern

He has no idea, then, that he's signing off on the fact that JFK gave hush money to Marilyn Monroe, that there was ties to the mob, that he has just kind of, in effect, put his stamp of approval that this is a bona fide chapter in American history?

John Reznikoff

His imprimatur on it meant that everything-- because everything was from the same archive and existed from the same barrel of apples-- was authentic.

Jake Halpern

John, isn't it possible that if you had come to him and said, look, this stuff that I'm giving you here is red hot. This confirms some stuff that people don't want to believe, and some of it is kind of incredible, that he might have said, all right, let me break out the magnifying glass and take a little bit of a closer look here. This is huge what I'm about to do.

John Reznikoff

You know, that I won't concede, because I think in knowing how a handwriting expert looks at things, either it is or it isn't. So either it was his handwriting or it wasn't. What it said wasn't important.

Jake Halpern

So the papers were authenticated and John laid the groundwork to sell them. He enlisted another dealer of historical papers and artifacts, a well-connected guy named Tom Cloud, to handle the actual sales. Lex would get most of the money. Tom and John would make up to 20%, which they would split evenly.

They came up with a strategy. They quietly sell the documents to Tom Cloud's roster of wealthy clients on the condition that they not disclose what they'd bought to anyone for a few years. Meanwhile, John and Tom would find someone to write a book about the archive, which would then lead to a movie deal. Once the book and movie were released, of course the value of the documents would likely skyrocket and investors would be happy.

Everything started to fall into place. An acquaintance connected them with the perfect writer to publicize Lex's archive, Seymour Hersh, the famous investigative journalist who had won a Pulitzer for breaking the My Lai massacre story. Hersh, as it turns out, was already under contract to write a book about JFK's presidency called The Dark Side of Camelot. Cusack began sending copies of the documents in batches, and Hersh started checking that the names and other details in the documents were consistent with his own research.

John Reznikoff

All of a sudden a document would come out and Hersh would independently verify that there was a name of a doctor that injected Kennedy with painkillers for his back, and that nobody knew this. And he found out the name of the doctor through somebody who he had interviewed. And it would be impossible for Lex to have produced that name or these names, like-- or the people who were co-signing the documents, or advisers to Marilyn Monroe that were being verified along the way. There was more confidence. The confidence was building.

Jake Halpern

And this was something they could use to build investor confidence, too. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Seymour Hersh is on board and has independently verified key parts of the archive. Hersh's book would come out in November of 1997. In addition, Hersh was working on a documentary about the archive in collaboration with ABC.

By the end of the summer of 1997, about 140 different investors had made purchases from Tom Cloud. The trust agreement between Kennedy and Monroe had alone sold for $450,000. At this point, the documents had already netted roughly $5 million. It was all going great. They were making a lot of money. John and his fiance got married. Lex's wife was a bridesmaid. And John had a baby boy. Then, one day, John's in Cape Cod and he gets a phone call.

John Reznikoff

August 22, 1997, sitting on the beach.

Jake Halpern

What happens then?

John Reznikoff

I believe that's the day. Now, I could have it wrong. It's either August 22 or August 27. And I'd like to know what that date is so I could say that's the day that changed my life. That's the call I get from Cloud about Lex being sandbagged by Peter Jennings.

Jake Halpern

Cloud is Tom Cloud, Lex and John's business partner. ABC's Peter Jennings had interviewed for Lex for a segment that would air on 20/20.

Peter Jennings

Where did the collection come from? The answer lies with Mr. Lex Cusack.

Jake Halpern

John and Lex had been excited about the segment. They saw it as a kind of phase one of their media launch.

Peter Jennings

Where you aware at any time before your father died that he'd done any work for the Kennedy family?

Lex Cusack

No.

Jake Halpern

What became clear very quickly was this wasn't just a puff piece hyping Hersh's book. It was an investigation. You might have heard something about it. It became huge news. What happened was that ABC had gotten wind of some suspicious inconsistencies in the archive. For starters, one of the letters from Cusack Senior, which was dated 1961, had a zip code in the letterhead. It turns out there were no zip codes in 1961. They weren't announced until 1962.

So ABC hired an expert of its own, a former documents examiner for the FBI. He did forensic analysis of the documents, scrutinizing the paper, the ink, the type. The examiner found that the typeface turned out to be something called Prestige Pica Selectric, which didn't exist until the early 1970s. And whoever typed these documents had also make corrections using a particular kind of lift-off correction tape.

Documents Examiner

And lift off tape was not invented or placed onto the market until 1973, a full 10 years after President Kennedy was killed.

Peter Jennings

So this is a blatant forgery by any standard?

Documents Examiner

Blatant forgery.

Jake Halpern

Jennings takes all this evidence and calmly and methodically presents it to Lex. Lex appears stunned, almost as if he can't process what Jennings is saying.

Peter Jennings

How do you explain that?

Lex Cusack

I really don't know. I don't know. This is a problem we grapple with often, is that are these the original documents? Are these copies that were made of the documents? Are these--

Peter Jennings

Throughout the remainder of our interview, Mr. Cusack offered various explanations for the problems we showed him. But the one that he repeated most often was that the documents we had questioned might be later copies of originals. What he meant by this was never clear.

Lex Cusack

So somebody might have put their signatures on those documents at a later time.

Peter Jennings

I'm not talking about the signatures. I'm not talking about the handwriting.

Lex Cusack

The documents themselves. I understand what you're saying.

Peter Jennings

We're talking about the typewriter technology. It was not available at the time these documents were allegedly drawn.

Lex Cusack

There must be an explanation of why those documents exist, if in fact, they were produced later.

Peter Jennings

Mr. Cusack, somebody has forged the documents.

Lex Cusack

I think quite a lot of the other experts will not agree.

Peter Jennings

I'm bound to ask you, Mr. Cusack. Did you forge these documents?

Lex Cusack

No sir, I did not.

Jake Halpern

By this time in the interview, there's a pregnant bead of sweat sliding its way down Lex's cheek. He looks desperate and trapped. If the camera panned out, you would half expect to see him manacled to the chair. So this is what Tom Cloud tells John when he calls him on that day in August.

John Reznikoff

My heart dropped out of its spot in my body at that point, and it was, oh no.

Jake Halpern

Here's the interesting thing. It's not, oh no, the papers are fake, or oh no, I've been duped by Lex. Its oh no, we've told the truth, and now we're in for it because we've antagonized the Kennedys, the one family in America you do not antagonize. Plus the mob and God knows who else.

John Reznikoff

This must be this very powerful family trying to prevent this information from coming out. And that there's no way that these are fake. That these are real. You know, Lex is a war hero. He's an honest and good man. This can't be. And this is a big conspiracy, and we need to get to the bottom of it.

Jake Halpern

The notion of a conspiracy might sound a bit far-fetched and frightening, but it also offered some assurances. At least in this scenario, the world as John knew it remained constant. The papers were still real. The choices he had made were the right ones. And Lex Cusack was still his dear and trusted friend.

John Reznikoff

That's what I'm thinking. And what seems like minutes afterwards, it's a grand jury investigation.

Jake Halpern

John hired a criminal defense lawyer and the two of them made a trip down to the US District Attorney's office in Manhattan. They met with the prosecutor, Paul Engelmayer. And even here, John didn't feel safe.

John Reznikoff

We went in. We went for the proffer session. I told my side of the story. I remember walking into Engelmayer's office, and on his wall was a picture of Kennedy on the beach in Hyannis. And that just in my mind was, oh my God. This is a set up. I'm going down because I've revealed the biggest secret of the last 40 years, and they don't want this secret to come out. So somehow they're going to make it look like I'm a bad guy. He's working for them. This is all a conspiracy. All these bells are going off in my head.

Jake Halpern

During this period, things got pretty dark for John. He began taking medication to reduce his anxiety and to prevent panic attacks. Still, he was paranoid. He became convinced that something terrible would happen to him, that his car would blow up when he turned the key.

John Reznikoff

I'm thinking that somebody's going to kill me, basically. That's what's going to happen. That this stuff was not supposed to be released, and there's going to be an accident.

Jake Halpern

And all this time, John is rehashing the Peter Jennings interview and the inconsistencies with the documents. The typeface and the zip code, the lift-off correction tape. What explained all that? The first chance he got he confronted Lex.

John Reznikoff

We met somewhere, I don't remember where. And he was holding his hands to his head. He didn't know what to do. He'll just give all the money back. Of course, he had spent most of the money then.

Where did these come from if they're not real? How could they be?

"I did it," he said. "I did it. It just got carried away."

Jake Halpern

He's confessing to you, I forged these documents?

John Reznikoff

He didn't say exactly that. He said, "I did it. I'm the one who did it."

And I said, "What are you talking about? How could this be? How could this possibly be? What are you telling me?" And then he recanted. He said, "I just said that because it was a moment. I didn't really do it. I don't know what this could be. Maybe it's a conspiracy." I don't know what he was saying. I don't remember, but he was equivocating.

Jake Halpern

What especially bothered John was something else completely. During the 20/20 segment, Peter Jennings had reported that ABC could find no evidence that Lex was a retired naval officer.

John Reznikoff

I mean, that was a big thing for me, the military thing. If he was this military hero, in my mind, these can't possibly be non-authentic.

Jake Halpern

When you confront him with this, what does he say?

John Reznikoff

On one hand he says, well, it was just kind of a story that got carried away. On the other hand, he said, well, there are things that I can't talk about. Like the indication to me was, OK, he was MI5 or that it really was real, but he was some kind of covert agent and he couldn't talk about it. It seemed believable.

Jake Halpern

Before you scream to yourself, how could he so stupid, consider that John's realization about Lex meant dismantling everything he understood about himself. John's entire career was based on knowing the real thing when he saw it. He could judge the authenticity of stamps, and signatures, and documents, and, most importantly, people. Especially friends. In other words, John was no dupe. No way. And not only was there a lot of money on the table, these documents were going to make his career. So while it might sound crazy that he'd believe that Lex was MI5, it made even less sense that John himself was a sucker.

John Reznikoff

I would hang on anything that would be a thread that would be, yes, see, I was right. Here's the record of him being a covert agent for the CIA in military clothing, or whatever would happen that would make this whole thing, the whole nightmare, end.

Jake Halpern

John's lawyer told him that he had to clear his name, and the only way to do that was to secretly record Lex. He needed to get him on tape discussing their earlier conversation where Lex confessed and then recanted. Because that would show the prosecutor that John was innocent. After all, Lex wouldn't be confessing and making excuses if John were in on the scam.

John at first refused, arguing that Lex hadn't done anything wrong. His lawyer insisted. And he said, well, you don't have to do it if you don't want to. But tomorrow, if you don't do it, it's fine, but you need to get a new lawyer.

John Reznikoff

I can't help but think that you know something. I can't help it. I'm sorry.

Jake Halpern

So John did it. His lawyer hired a private detective to wire John's office with a hidden microphone. He and Lex talked for an hour. They're both tense and emotional. Lex leaps from topic to topic, offering one wild, half-baked explanation after another, while John tries to pin him down.

John Reznikoff

The thing that I can't get out of my mind, what's bothering me that I can't get out of my mind is when you came here-- what was it-- three days after. OK, you're sitting there, and you're telling me that you're guilty, that you did everything, that everything's fake. You've got to listen.

Lex Cusack

I'm listening to you. I am. I'm listening to you.

John Reznikoff

Lex, I'm telling you, I'm looking at my son's picture.

Lex Cusack

I know. John, I know. I'm looking at your son's picture. I'm looking at you. You don't realize how close I feel to you. So I'm looking at you and I'm going oh my God. I've ruined this guy's life.

John Reznikoff

Well, that's true.

Lex Cusack

OK, so I'm going oh my God.

Jake Halpern

Lex tells John he only confessed in order to protect his father's reputation. He didn't want anyone thinking his father had forged the documents, or that his father was somehow connected to the mob. Though, maybe his father did fake some papers for whatever reason.

Lex Cusack

I'm thinking like, people are going to think my father's a mob lawyer. My brother's going to think he was a mob lawyer and that he forged this stuff to protect himself from getting in trouble. And now it's all like, I can't let that happen. So it's more like what if we just say, we'll give everything back and the whole thing will go away. We'll just pay everybody back, it was a big mistake, we don't know what caused it.

It was like I was having a nervous breakdown practically. I couldn't figure out what the hell-- it was such a shock. What could possibly have happened? Could my dad have done this? If he did do it, [UNINTELLIGIBLE PHRASE].

Jake Halpern

Lex seems generally confused. The only thing Les essentially admits lying about is his navy career. He tells John it was more or less a joke that got out of hand until a number of people, including Lex's own wife, were under the impression that he'd actually fought in Vietnam. The thing barely hangs together.

As for the crisp, white lieutenant commander's uniform that John had seen him wearing that day in Annapolis--

John Reznikoff

Where'd you get the uniform?

Lex Cusack

[UNINTELLIGIBLE PHRASE].

John Reznikoff

That gives you a military uniform with your name on it and everything?

Lex Cusack

I didn't have my name on it. It had a name tag.

John Reznikoff

And the Navy cross?

Jake Halpern

Lex didn't want to comment for this story. So all I have to go on from him is the TV footage and the wire recording. There, Lex mostly comes across as pathetic. He doesn't show any of the smooth cunning of the Hollywood con man. Instead, his genius-- if that's what it is-- is his lack of finesse. If he's conning John, and his disguise is the pitiable friend who got in over his head, then he plays it very, very well. So well that after the secretly recorded meeting, John says he didn't feel relieved or justified. He felt awful.

John Reznikoff

There was an Irish pub on the street over from my office, and I remember drinking three Guinesses in like 10 minutes. And I'm not a drinker. I was like, wow. What did I just do?

Jake Halpern

Is there a part of you still believing this guy could be a decorated navy officer who has the real documents, and I'm betraying him?

John Reznikoff

I think there's still, like-- I don't know why, but like a 1/100 of 1% part of me that still thinks that.

Jake Halpern

John says the real aha moment for him finally came with an FBI agent told him point blank that Lex had never served in the military. In other words, Lex's best move, whether by luck or design, was that he hit John's Achilles' heel. He passed himself off as a decorated soldier. So Lex's deepest betrayal wasn't the JFK papers. It was claiming he breathed through a reed in Cambodia.

Lex was convicted in federal court of mail and wire fraud and served nearly 10 years in prison. He got out about three years ago. Seymour Hersh's reputation took a temporary hit, especially after he testified at trial that he quote unquote, "misstated things regarding his independent verifications."

John was cleared of any wrongdoing, but his life didn't just bounce right back. His business suffered. He had to resign as President of the Professional Autograph Dealers Association, an organization he founded. His marriage fell apart. The JFK papers nearly ruined him. And-- it's not surprising-- he's had a hard time trusting people since.

John Reznikoff

I definitely have trust issues in my life. There's no question that I have trust issues because of this. I mean, you get paranoid. Is Lex my friend because I'm such a great guy, or is it because I was a foil in his plot to take over the world? And then I'm thinking, is this person really my friend who really is my friend, another person in my life? And I do do that, and I feel terrible and guilty about when I'm distrustful and I shouldn't be. But it's there. And I have to temper that all the time.

Jake Halpern

But in a weird way he's thankful too. His paranoia made him better at what he does. It was after the Cusack fiasco that he threw himself into studying fakes and forgeries, and made himself so good at spotting them.

When I show John a copy of one of the Cusack documents, he started to analyze the handwriting all over again. It was a document from an archive that had fooled so many experts and that some people in the field, even to this day, argue is real. He turned the paper upside down just as his mentor Charles Hamilton taught him to do, so you aren't distracted by the actual letters. You just see the lines, the curves, and the dots.

John Reznikoff

Now, the Js were always different, but look at the Jack, for instance, upside down. And just look at the way the spacing, and how it's inconsistent and bouncy. It's very, very good. The forgery is very, very good. I have no idea how they were made. No idea. That, to me, is the big mystery in my life. I don't know how he did it. I don't know how they were so good. I have no idea. Or if he did it. I don't even know that he did it. Maybe somebody else did it and he pushed them forward.

Jake Halpern

How hard is it to pull off what Lex pulled off?

John Reznikoff

I don't think anybody has ever done that in the history of our field as successfully as he did for the amount of time that he did.

Jake Halpern

And how was he able to do that?

John Reznikoff

Sheer genius, I'd say. Sheer genius.

Jake Halpern

And perhaps Lex was a mastermind. But then again, we all want to think we can only be fooled by a genius.

Ira Glass

Jake Halpern is the author most recently of the book World's End.

[MUSIC- "I'M GONNA FILE MY CLAIM" BY MARILYN MONROE]

The song stylings of Marilyn Monroe.

[ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS]

This American Life is distributed by Public Radio International. WBEZ management oversight for our show by our boss, Mr. Torey Malatia. In the mailroom this week, I was surprised to catch him opening a love letter he got from some random listener.

Man

This is not unusual. I can't tell you how many people have come forward over the years. I probably have three or four dozen examples of that.

Ira Glass

I'm Ira Glass. Back next week with more stories of This American Life.

Announcer

PRI. Public Radio International.